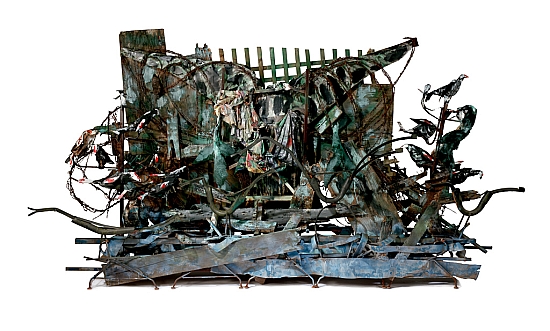

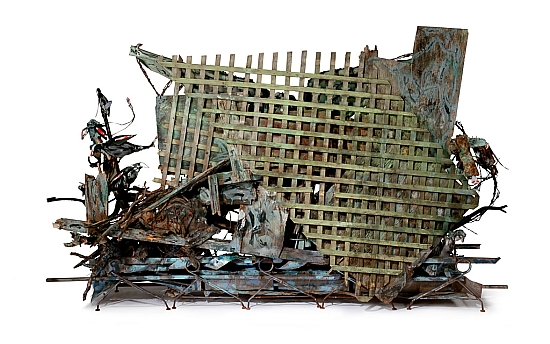

In this monumental floor assemblage from 2004, a metaphoric river becomes the setting for a parable on the struggle over life’s resources, here symbolized by the principal medium of life: water. Created from old blue-stained lumber, driftwood, and tin, Dial’s rickety stream hosts an odd gathering of avian characters, each vying for sustenance in the crowded ecosystem of their dusty water hole. Flocks of red-winged black birds compete for a place to search on welded metal bushes at the edge of the water, while iron egrets wade through wooden swells unaware of a dangerous driftwood crocodile lurking just beneath. Negotiating one’s way in the world can be fraught with peril.

Suspended overhead is the giant American eagle with outspread wings, an image taken from the United States dollar, which, for Dial, symbolizes the freedom to acquire a good life. This once powerful emblem of equal-opportunity-for-all now hangs lifeless. The death of democracy’s promise, its limp body is being poked and pecked by two voracious buzzards. These scavengers are made of carpet wraps to reflect their lowly stationed painted money-green to signal their acquisitive nature. For many, buzzards might represent greed and depravity, but in Dial’s art, they are strangely laudable creatures. The ultimate opportunists, who are ready to feast on any piece os carrion, these birds of prey are also skilled survivalists, able to make good use of whatever limited resources remain at hand, which is sometimes the only creative response to struggle and deprivation.

Dial’s water scene also evokes a sense of boundaries and exclusions. Festooned with barbed wire and framed with fencing, it illustrates the life barriers that must be overcome by those who struggle at the bottom of the social hierarchy. In particular, the barricaded river conjures up memories of segregated water fountains, public beaches, swimming pools, restrooms, and eateries, all sites for white racist fantasies regarding pollution, taboo, and contamination, and all places where, in the not-so-distant days of the Jim Crow South, water was once offered to some and refused to others. —Joanne Cubbs