Asberry Davis

About

I was born in Garnett, South Carolina, Hampton County, down by Savannah, Georgia, in 1918. I been living in this place, Boyer, out of Holly Hill, since 1959.

When I was little, my mother was sick a lot, and I had to stay home, take care of her, and missed most of the schooling. School back in that country at that time didn't run but three months out of the twelve, noway. When I did get to school I had to walk about six miles. Wasn't no school bus then. Many of the little blacks had to walk seven, eight miles, or more, look at the school bus pass by, white children on it. School buses wasn't comfortable as is now, but better than walking. Bus's body was old wood. Wood seats. No heater when it's cold. But we'd rode it if we could. That's back about '22 or so, I'm talking.

First work I was doing: minding cattles—big ones, little ones. I was about eleven years old in Estill, next town to Garnett in Hampton County. Then I went to working on a farm about five years. Left there, went to working for a lumber company. Got off from that, went to working on a state highway. Helped build 1-95 out there. Then the railroad, Atlantic Coast Line. It's Seaboard Coast Line now. So many scatterings of jobs I'd work on less than two months and go on to something else. Never settled into nothing. Never liked any of it much.

The Atlantic Coast Line was paying big money at that time. That's why I kept at it there. Seventy-five cents an hour. All the other jobs was a whole lot less than that. Atlantic Coast Line in 1947 had a crooked foreman from Birmingham, Alabama. He stuck me for a whole payroll. Wasn't nothing I could do about my money, and I never did get it. That's the last time anybody stuck me out of my work money. You know, ain't no good working when you don't trust him that you work for.

I been making stuff since I moved out here in 1959. The first time I tried to build some important thing was the grave for Ella Riley. That was '73. Ella Riley, some people call her "Mother Ella," the old lady I took in, lived in this place. She fixed up herself a place in those woods back there.

Her husband, Abraham Riley, died six or seven years before she died. They lived in the quarters right near the cement plant right up until he died. She lived by herself about two years. She was an old lady having it pretty hard, and I was here by myself and said I'll take her in. She was a lot of help to me for three or four years, and then she died. Ella Riley had always wanted to go back to her home county, Beaufort County. That's where she say she want to get buried. When she came sick she say to me, "You done had so much trouble with me, after I die just bury me wherever you want to."

It was bad weather when this lady died. It was in the month of February 1973. It was snowing. Biggest snow in this county come when she was laying up in the funeral home. Couldn't nobody get buried because of the snow, six or seven bodies backed up at that home. Snow high up on the ground. We had intended to bury her in a different cemetery, but that was a bad place. Some people get bogged down, being near the swamp. Somebody said, "Briner Church is a good place, on a hill." That's how she got to Briner's cemetery. They say Briner's used to be a white folks' church but they turned it over to the colored.

Ella Riley had done told me, "I got all these things in there, my possessions, I want you to put it on my grave. You got to do that." So I built her this thing out of all of it, gave it a fence, a gate, a regular little place for her. Arranged all of her possessions.

She had bought some cloth from a lady in Orangeburg about a month before she died. I put it all right there around the cypress tombstone I carved for the front of the grave. I made one at the back, too. I been back over there a couple of times to straighten up, but mostly I just leave them alone.

Before I came to this place here, there was a church, many years a church, goes all the way back to slave times. This place was given for that reason. It is a place of God. It is near a place where the railroad track and the drain creek cross the highway It have had many pastors. It was a church in the outdoors. Peoples, colored and white ones, have come here to pray. I was the last pastor. I'm the last man and the oldest one living, if any's living at all. I can't think of one still living that used to come here. The church got destroyed. I was in the hospital, and robbers tear down the place, took everything. Tear down the concrete altar, took the money—about twenty-five thousand dollars. I figure they come for the money, then destroy the whole place to get rid of all the evidence. They stole all the books and paperwork and three old Bibles, all the church records and information, something in it concern every one of the pastors.

I was in the hospital. One of the head nurses ask me, 'You been operated on and here for three, four days. Did you give anybody authority to bother anything you left at the church?" I say, "No, nobody." She say, "They down there tearing down the whole place." I got out of there and rode my bicycle straight here to church. It was a mighty cold night I come up on the robbers unexpectedly. The nurse lady had said, 'You'll know them all when you see them." I know all them except two of them. They had drove their automobiles up in these woods and was hauling out anything that could be hauled: the seats, the altars, the things I had done put up, every bit—even the bathtub that sit out there. I had a good bathtub out here before. A house had burned down and I bought the bathtub from the people. It was good as new. I had put it up as extra room, they call it an anteroom, on the altar. That was it, the end of the church. I had got inspired to put my place right back here by the church. I was so disgusted when I got the news. But I never looked back. That was in the ‘70s.

I was contacted by angels from heaven about 1995, down there between Dorchester and Colleton County late one night. I came in contact with a group. I thought it was regular people. I was riding my bike, and a flying object followed me—object about as big as a buzzard, with lights all over. It agitated me all the way from St. George to Walterboro. People was parked all along the road and ask me if I seen that bird thing. I was wishing it would tangle with some of them people in cars and stop bothering me. Then I came upon what appeared to be a man motioning to me to come over. He was walking on the side of the road, and I was riding when I saw him. This person appeared to me, and I put on my brakes. I said, "Yeah?" when I pulled up to him. He said, "What you doing?" I said, "Traveling." He ask me some other little questions like how far and how fast I'm traveling. I thought it was a man, ordinary, but after, I said in my mind, That was an angel. It worried me in my mind, you know. I just wasn't sure.

It tackled me again in 1996. This here had appeared to be a man and a woman. They asked me how far had I come from. I told them I generally ride about eighty miles a day; after eighty miles I get too tired. He asked me was I hungry, and I said, "Not hungry. Tired."

The man said to me, "Follow us. We got a special place to take you.”

I said, "I'm tired now. I'm going to lay down right here." I was by a cemetery next to a big old church. He said, "Lie here. I'll bring you something to eat.”

I wasn't expecting them to come back, but he come back in about fifteen minutes. Brought me three containers of food. I was surprised. People who say they are going to give you something to eat usually do not. He said, "When you get through, you can leave the containers or take them with you." I kept the three containers, got them here now. When you get food from heaven, you keep the containers.

Next to the cemetery by that old church there was a big bulletin board. Wrote on the bulletin board was "Welcome to the dead and the ignorant."

I was ordained by the angel about one o'clock at night in the middle of the road. Ordained to put those things out here by the railroad tracks at the crossing. It has a lot to do with where it is, near that railroad track and those woods. I met some people about a hundred years old when I first come up here. They say it could have been there two hundred years, the railroad tracks.

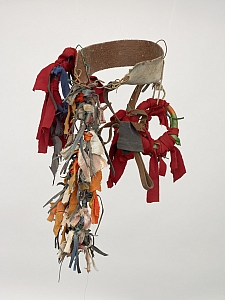

I make things also to dress up in. Different things can give me different strengths. I wear certain things every day, and I keep some for special days or needs. When I dress up in a full outfit, you'd say, "Where the devil did this man come from?”

I got this bracelet set I wear every day, This here, this iron one right here, is made of a German steel; you can't cut it with a blowtorch. The rest is rubber—hard rubber. I'm not a violent person, but if you come in contact with a person who wants to be violent, I can hit him around the head with these. It ain't going to kill him, but he will fall down and not come back too quick.

I got these things I make—rubber circles, leather—all wrapped up and tied up with the cloth from my old clothes and stuff I find and pick up. You can pull it over your head and wear it around your neck like a collar, or put it on below your feet, go all the way up around you. I call these things a "belt assembly." One of them here is made out of this old chain and a money purse, with iron and rubber. It has its special time, too.

I hang the wearing things on the trees. I got my reasons why I do things but I don't always talk about it. I got hats hanging, hats I have made, what I call a "scat." A scat is something that ain't worth much of nothing, make you look ugly or funny. That belt I'm wearing look like the devil. I ain't made it for no good looks, noway. The devil come and claim his own.

A man got to know his power, got to test his strength. I have thought up some ways for doing that. I made up these games, you know, one man pull against another man. One man put his strength against another one and his mind against another man's mind. I made these things for different games like that—sometimes four men pulling for strength.

I used to work at a lumber company and use their machines. They had this one, called it "Highball 99." It pulled logs. Last one I seen operating was in 1938. It give me the idea for something I named the "pulling rig." Each man have one of these poles, about fifteen feet apart. Each one pull the other, with a "royal stake" in the middle. The man that pull the other to the royal stake, holding him there for five minutes, he the one wins. Sometimes it come out tie—tie, neither one defeat the other.

The pulling rigs is all different, but all of them got things that represent strength. Same with the equipment I call the "stretchers." They are solid steel rods, decorated and helped with other stuff and weigh similar—seventy, eighty pounds. The weight of it is the life of it. When you know how to use it, when you getting pulled to defeat, you plant the bottom forks in the ground and you can't be pulled no farther. Your man got to give up.

When you rig up in the pulling gear and you go out not to be defeated, I got this special belt assembly you wear, the orange one. I been defeated about once or twice, exactly don't remember. A man don't want to be defeated. You go to a ball game and look at the man who's been defeated, he's all downhearted. The winner is happy.

I'm eighty years young now and never met a man that can stand with me. But the Bible say one must not praise ourself, let others do it. I ride my bicycle every day. I ride to Charleston, Columbia, Savannah. I know all the roads. I go around and pick up things, and I make things. I pick up different objects, might be a little wrench, might be a big piece of iron. First thing pop in your mind when you see something: "What it good for? What might it be used for?" You got to be your own judge on that. You got to wrestle with the problem of what can be taken. And some things you react to it according to the way the general public feel about it. You got to decide what the people going to think when they see something, what you want them to think. What you think about it your own self. I don't know exactly what is in the books out there, but I know something about what things mean. I think soberly but not too highly.

I make things just to amuse me, that's all. There's billions of people in the world. No two are alike. You run your own way.

Taken from interviews with Asberry Davis by William Arnett in 1998.