Jessie Marshall

About

My name is Jessie Marshall. I was born July 8, 1936, right here in this house, in Woodbury, Georgia. My daddy was a coal miner. I was the first kid. My daddy’s mama cooked up on Best Mountain for Mr. Bray and them in the big house. We moved to Kentucky where the coal miners’ jobs were, my daddy and also my grand-daddy. Daddy went to do coal mining. Grandpapa had left: my grandmother I called her Ma Emma, she was like a mama to me—he left her over on the mountain. Grandpapa went and met a woman in Kentucky—named Miss Virginia—and they took care of our house.

My granddaddy had a gambling house up in Kentucky and was selling whiskey. That’s where my mama always stayed. I had to take care of all the kids at home. I was put in school in Jenkins, Kentucky, and went to school with white children over there. It was nice in Kentucky, lots of work for my daddy. I used to go dig that clay up on the hill behind the house and get the coal rocks out of it, and make stuff out of that clay and them rocks. That was something else to see. My first stuff echoes in them hills.

When I was about second grade we come back to Woodbury. Down here we had to get out of school at twelve o’clock and go to the fields to work—pick cotton, pick peaches. When we was kids, kids had to work.

I worked in a meat-packing house down in Manchester when I was about thirteen, or twelve. I worked at the Foundation over in Warm Springs, in the cooking department. Franklin Roosevelt was already dead. The job I liked best over there was working with the little children with polio, like that, and also pushing the older people’s wheelchairs and stretchers to the movies at the Foundation.

When I was fifteen, that’s when the Korean Conflict started, me in the fire department, in Lincoln, Nebraska. We had one little place that black people could go to get your beer and stuff like that. You could get you some trim, stuff like that, right across from the police station. One night the police put all of us in jail and never did say why.

It was a big stroll up there to Omaha, and lots of black people got on that. My friend Wilcox was messing around with this woman in Omaha. She was young, just a friend, but a pretty thing. I was drunk one night and I just married her. We never did—how do you say it?—complete the marriage. I might have seen her one more time after that, and then she went to her sister’s in Venice, California.

After I got discharged I came on back to this house in Woodbury. Soon as my discharge checks come, I was gone. Went to Atlanta, went to work for Davis Brothers—they was cafeterias. They didn’t pay you nothing; you just worked for tips. Later on they gave you a dollar a day. I worked up to head waiter, working at the Harvest House, and made me fifty dollars a week. I was writing numbers for Mr. Woods, a white man, a good man, over at the restaurant. He was my main man. Another man, Whitey, come with all them pretty girls with him, he wanted my business, but I stayed with Mr. Woods. Mr. Woods had the best business, so they killed him. Glenn, a black guy I got started writing numbers for Mr. Woods, he had become Mr. Woods’s number two, and I was the captain. After Mr. Woods was dead, Glenn moved up. One night he was playing cards and somebody came with a gun and killed him. They said he died of cancer. I got myself out of that stuff, said to myself it was time to quit.

I had me a new car back there, a Dodge Dart, and started going around to meetings and things, you know, in the church. I always was up under the Baptist thing and believed in prayer. When I was a little kid, the preacher, Reverend Cook, used to come around, and the children have to go outside. We didn’t get chicken to eat but once a week, and the preacher always got the first shot at it. Always got to the table first.

When I was waiting tables in Atlanta, they started calling me “Preacher,” them peoples I was serving. And I was thinking I’d like to go to preaching. I been had my mind on it since I was a little kid. My uncle, Uncle Long, had cleaned up at the Sanctified Church down in Manchester, and I had helped him, and I had wanted to get into preaching and be a boy wonder. I thought about it all the way. My grandmother, Ma Sula, my mama’s mama, she was a strong believer in that stuff. They used to do speaking in tongues, but I didn’t understand none of that. A man named Reverend Reno used to come down here from Atlanta. He was supposed to be my uncle. Him and Ma Sula, four or five of them, Mrs. Render, she stayed up that way and come down here sometime, go in there, have their little “meeting.” I tell you, I don’t know what went on in there.

So while I was waiting tables I was getting into the words. I was on radio on Sundays, telling people about the blessings, and giving out the numbers right and left, just like that. They come to to me for advice on numbers, and that’s how I made my money.

I met Bishop Notae. George Eaton was his name, called himself Notae—Eaton backwards. His mama was in charge of the NAACP in Birmingham. Bishop Notae had went to Chicago and had met Prophet Shane. I met Bishop Notae first. Me and him got to be friends, and Prophet Shane I met later. Prophet Shane got mad at Bishop Notae for teaching me about how to be talking to peoples, teaching me the spiritual work, all that. Shane didn't want me or nobody else learning that stuff. There wasn't none of them in the South back then that know that secret preaching stuff. Don't too many know it now, even. Some people get into it think they know how to do it, just mess it up.

Notae, he got killed, too. We had that radio show on Sundays, and he had a crew, and they drink liquor all the week. Notae liked to be in the alleys, man, looking for women. Said he had a kid in Atlanta. He was a little old guy, kept his gun with him. Somebody turned his own gun on him. Killed him. You know, you live by the gun, you die by the gun. He was a smart guy, a real good man, Doc. Over in Fourth Ward I think it might have been. Might have been one of his lady's fellows. You know how it work.

I'm the one that put 'em together,

Break 'em up or run 'em right out of town.

Put bread in the breadbox,

Meat in the icebox,

And money deep down in your side pocket.

I'm the man with the long hair

That can put you there,

From Algiers, Louisiana.

I did everything for him in Atlanta. Put out his handbills, take him to the church, chauffeur him around, do anything he needed to be done. Put his robes on for him. Hairy little man, not exactly black, looked like a Mexican. Only drink vodka, didn't fool around with nothing else.

Prophet Shane looked like a Mexican, too. Funny-looking man, might have been a hundred years old. Say he's from Georgia—Sandersville—say his brothers was whipping on his ass so he left for Chicago. Worked up in Jewtown. They get up on boxes up there to preach or demonstrate or sell stuff—incense and stuff. Good stuff come out of Chicago. Shane was a mysteryfied fellow. Got whatever he wanted. He did all the women, drugs, drink; ain't nothing he wouldn't do. I was right there with him. I'm not going to lie about it.

They took my Cadillac in Atlanta. Black detective, J.D., took it for the Man. Said there was stuff in the car. Might have been a joint or two. So me and Shane, we went on down to Miami. I went to preaching on the radio. Reverend Ike was on the radio back then, preaching against the root bag. I go on the radio and say, "The root bag made from the cloth, the cloth come from the cotton, cotton come from the root. Prayer is the key. The rest is just symbols. It's all the same. It all come down to prayer."

I met Mary, my wife, in Miami. She was from Thomasville, Alabama. She just as sweet as sweet could be. When you kiss her it was just like sweet milk. Just a sweet, good girl.

They was bringing black girls on buses down there to Miami Beach, to the "Premises." That's where they stayed. The girls worked at different houses, and all the girls lived together and knowed one another. Intelligent girls, too, man. They came from Alabama, Georgia, all over. They all had their day off, Thursday, all came into town. That's how I met Mary. Mary was messing around with Dave Bunning. He was the main man for Miss Polly Davis, a white lady that owned all the Miami Buffet restaurants. Mary went with me.

Mary, she the one put me on my knees, man. Make me got to pray before I get into bed. I brought her here to Woodbury. She and my mama got to be real close. I left her here and went back to Miami. Mary stayed here ten years with my mama. We had two kids, Michael and Vincent, and they went to school here until they left here and went back to Thomasville, Alabama, with their mama.

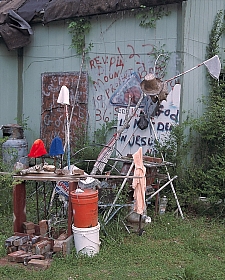

Back in Miami I waited tables and went back on the radio. I had meetings at the Longshoreman's Hall—spiritual meetings, demonstrate, do all that stuff. Father Abraham was there, out of Jacksonville. We was on the radio same time. He brought them in. He had himself a big pulling hand. I opened up a studio on Forty-fourth and Seventh Avenue, red, white, and blue, Queen Elizabeth Religious Studio. I got the red, white, and blue from Daddy Grace House of Prayer. First time I see those colors used like that.

I did some good stuff in Miami. I was in love with a woman there, showed me a whole lot of things, but she stopped helping me. Things quit going so good. My place got burned down, and I just said I'll come on back home.

I come back here to Woodbury. I wasn't intending to do nothing here, but I got caught up in this town. I come to see my mama, intending to be here two or three days and I wanted to go to Atlanta, but then I got shot.

I went up to the whiskey store for a pint of gin, went over to Mrs. Moody's to drink it. I got it all in me, and Frank, a railroad worker, was driving me. I had got in his car to get me something to smoke. Frank hit me with a stick and I grabbed him. When I turned him a-loose and got back from him—giving him a chance, Doc, the worst thing to do—that's when he shot me. I had to stay in Woodbury, have operations and go through hard times, and I been here ever since.

I set myself up here, and word got around. See, I been a prophet since I was a little kid. When I joined the church I took eighty-five folks with me. That was when I was a little boy. People around here tell one another all different things about me, and peoples started coming to me from all over. Come for different stuff. Some want to kill peoples. Some want to get insurance money. Lots of them be sick, got different conditions on them.

Most peoples don't want you to read them. They tell you what they want you to do. They want you to just listen. They tell me who they is. They analyze themself to me. Mostly they pay me to listen. But I don't take all cases. I ain't Jesus. Every now and then I get somebody want to do something. They recognize that I know stuff. I can help them, Doc.

Taken from interviews with Jessie Marshall by William Arnett in 1998 and 1999.