Leroy Person

About

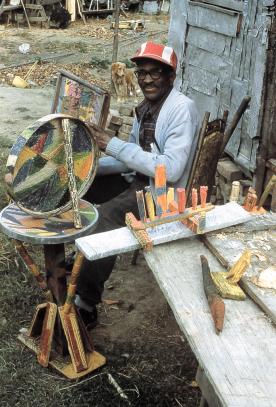

Leroy Person lived near the Albemarle Sound in northeastern North Carolina, in a swampy locale called Occhmecchee Neck, a place so humble it is ignored by official maps. After sharecropping as a young man, Person worked many of his adult years at a sawmill until lung ailments forced him to retire early. Late in life, after decades of observing the effects of saw blades on wood, and with little else of importance to occupy his time, he began to carve wood at home using humble tools such as hand saws and pocket knives. At first, he carved his house (which he had also built), applying gridlike, cuneiform incisions to window casing, exterior doorjambs and lintels, and the porch’s posts. The transformation of his property grew to include a perimeter fence made of carved tree branches. Later he removed all this work; largely through the encouragement of a neighbor, Ozette Bell, he subsequently resumed carving. Ultimately he became extraordinarily prolific, not only reworking his living spaces but also creating hundreds of discrete sculptures, carved furniture, rubbings of his woodwork, and crayon drawings.

Person’s carvings gradually organized themselves into several categories. There are carved plaques with grids and webs of chiseled or whittled lines. He also used the plaque-carving technique in making furniture. He usually worked on existing pieces of manufactured furniture, especially cabinets; at other times, he assembled furniture, including chairs he called “thrones.” There are also freestanding sculptures of massively miniature, anthropomorphic, and zoomorphic figures (birds, fish, and snakes were favorites), as well as small tabletop tableaux comprising groups of stylized, usually humanoid figures.

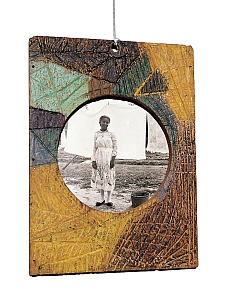

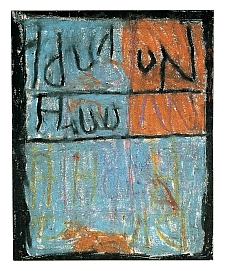

Leroy Person’s sculptures consistently employ circles (signifying the sun and saw blades), images of trees (“lily bushes” or “God-trees”), representations of his tools (especially the wrench), and letters and numerals. Partially schooled, able to read and write at a rudimentary level, Person was one of millions of paraliterate African Americans in the southern United States. According to folklorist Roger Manley, who knew Person, the artist’s writing system was secretive but could be decoded by Person and selected family members. Manley notes that Person’s inscriptions often turn out to be mundane information such as telephone number and addresses, a fact that only deepens the mystery of the relationships among otherwise abstract works of art and specific individuals from the artist’s world.

Person's second wife, Frances, whom he married in 1958, was an accomplished quilter, well versed in the extremely asymmetrical, almost boastfully improvisational African American quilting style unique among the world's visual arts. There has been no research into the ways aesthetic influences worked between the Persons—Frances says she and Leroy never discussed his work—both artists shared a love for circle motifs, codelike clusters of line segments (think of bar codes), and compositions that defy a single dominant upright aspect and can be appreciated from all sides. Meanings and messages, therefore, seem to abound in her quilts as surely as they do in his plaques.

Person became such a prolific and compulsive creator that when he was hospitalized for lung disease in 1982 and had no access to his tools and wood, he began to draw with crayons on paper and cardboard. After infirmities stole the strength he needed to carve, he increasingly concentrated on his drawing. Although he did not live long enough to produce a body of works on paper comparable in quantity to his carvings, the extant drawings often masterfully manipulate line and color—two qualities that survived and prospered from his transition to drawing. Other emphases of his carvings lived on in these drawings' added refinement of his love of calligraphy. In the works on paper, Person most fully demonstrates the connections between his writing system and the quilt aesthetic. The flow from writing to quilt—or quilt to writing—is often patent. In several cases, quilters' motifs arrive unaltered in Person's drawings, such as when he included the quilt pattern known as "the box" in an untitled drawing.

Although the decades spent in the sawmill provide the clearest inspiration for his carving style—his waffled cross-hatches sometimes look exactly like the patterns found on well-used sawhorses—Person also wove baskets, sometimes from metal wire. That familiarity with the basket-weaving process is apparent in his carvings: Person most likely had some training in the craft, for the technical complexities of basketry ensure that few basket weavers are self-taught. The tree-branch fence, though not surviving in any known photographic record, was likely a monumental reconciliation of basketry, root sculpture, and woodcarving. (Thornton Dial has similarly reported surrounding his home with a fence of branches, which he says was woven in a herringbone pattern to suggest fish skeletons, and which he, like Person, destroyed because no one else appreciated it.)

Throughout his life, Person may have intermittently made wood carvings such as ax handles. After his retirement, his first serious artistic undertaking was to carve his home's window casings and the posts and lintels of its doors. He gradually covered his entire house inside and out with carvings. He surrounded his property with the fence of carved tree limbs. When combined with the immensely complex vectors of his carved lines, his use of secret writing, and his symbols, Person's carved house becomes one of the most unique recontextualizations of an African American tradition that uses collaged newsprint on houses' inside walls. Most often these collages performed roles as a spiritual defense against roaming souls (in addition to a thermally insulating function). It is not necessary that Person was consciously attempting to create a protective system for his house, as an artist like J.B. Murray did. It is not necessary that Person believed in haints—yet, according to Roger Manley, witches were one of Person's common subjects, and Person made carvings that depicted his dreams. Because the technique of dressing homes with improvisational grids of collage was so prevalent in the South, Person's home may be imagined a propagation of the tradition's forms if not its meanings.

However, the fact that his first carvings were on windows and doors, that he created the fence of tree branches, made double-sided rubbings to hang on the walls inside the house, and created runic, bent-wood inclusions to "seal" the crawl space beneath his house (real animals could easily pass through the wooden bars) strongly imply together that the purposes of his home adornment were something more than decorative. Moreover, he carved even those surfaces of his work that would not be visible, such as the bottoms of furniture. The fact that Person's signs often contained only generic information in no way contradicts the protective aspects of scripts and collages in other houses; many informants have emphasized that the content of the writing does not determine its spiritually protective power.

Seldom has any artist, regardless of background, combined such an obsession for surface articulation with a gift for modulating positive and negative spaces in lyrical, and frequently minimal, abstract terms. (In the Western tradition, Giacometti comes to mind, but his works' surfaces lack narrative or allegorical responsibilities to accompany their function as abstract textures.) One of Person's Peacock sculptures, which somewhat resembles a door lock from the Dogon peoples of Mali, exquisitely balances disparate forces: the menhir-like mass of the tiny wood plank; the cool contrast of rust-colored and black zones of color; the spidery, metal support legs; the technically virtuosic, looped incisions on the 'wood's surface; and the triangular configuration of drill holes that suture the sculpture's two faces and allow light to pass through. Line, color, mass, texture, and materials flow seamlessly.

Leroy Person's chip-carved motifs move beyond the formalist patterning typical of chip-carved sculptures. His patterns almost always include pictorial and alphabetic elements subsumed into surface topography. Person seems to have realized his surfaces' duality—their decorative and representational duties—and took the ingenious step of making numerous rubbings of his plaques. Many of the plaques would also make stunning woodblock prints, combining the Expressionist high drama of Die Brücke with the carefully reasoned symbolic arguments of Harriet Powers's appliqué quilts.

Furthermore, unlike many sculptors, Person was a sensitive colorist. Sometimes he painted his works, but most often he used wax crayons vigorously rubbed on and into the wood's surfaces, creating effects reminiscent of encaustic. Wax accretions form a shimmering patina that cheap paints could never hope for. In Person's sculpture, the color and texture of the crayons and rubbings are as significant as the carving; in some cases, color exists independent of, or in only distant relation to, the carving.

Leroy Person's stereotypically rural and simple life begot a deceptively complex artist who mastered a breadth of media and techniques, and who drew upon a wide range of sources (his love of television is often cited by relatives), many of which remain to be investigated. While grading lumber at the mill, he must have stockpiled in his mind untold numbers of carvings-to-be. When the tragedy of lung disease struck him, he considered it also an opportunity to begin carving in earnest. This mild-mannered man thereafter left behind that part of himself he most treasured: an artistic universe boundlessly intimate and tactile, with a dash or two of the grandly inexplicable.