Rev. Herman D. Dennis

About

Michelin’s Green Guides are essential to European travel for anyone interested in art and architecture, cultural history, or other information relating to a village or city, a mountain range, a battlefield, or the site of a religious miracle. The guides’ rating system (three-star maximum) is consistent and reliable. Devoid of hype or flowery language, the guidebooks profess interest in the facts alone, and they read as if they could have been written by a computer or a person who has never smiled. Yet when describing amazing and unique little town at the heel of the Italian boot, one edition of the Green Guide tells us that Alberobello “seems to have been built for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by Oriental magicians.” Sometimes a place defies sober description.

Margaret Rogers owned and operated a grocery store on Washington Street, on the north side of Vicksburg, Mississippi. She was born nearby in 1915. In the mid-1950s, she and her first husband, Abie Lee Rogers, built Margaret’s Grocery, their simple place of business. It was a no-frills, essentials-only little store that catered to the sparsely populated, all-black area on the outskirts of Vicksburg, a small strategic river city whose fall to Grant’s siege hastened the end of the Confederacy. Where Washington Street, Vicksburg’s cross-town thoroughfare, prepares to link with U.S. Route 61, the two roads create a defining, symbolic site—in this case, a place where a genteel, elegant, lively southern town (now less genteel and more lively because of the recent appearance of a number of palatial gambling casinos along the Mississippi River) dissolves into the flatness and emptiness of the seemingly endless Delta cotton fields. Somewhere in there is Margaret’s Grocery.

Go north on 61, take a left at Rolling Fork, head toward Mayersville on the river, and you will pass the fields near which Herman Don Dennis was born in 1916. (Over in Rolling Fork were born the artist Henry Speller in 1900 and the blues singer Muddy Waters in 1915.) Dennis had been called simply “H.D.” during his younger life but now he is called “Preacher” by almost everyone who knows him well and “Reverend Dennis” by almost everyone else.

He has been preaching since he was a teenager, and was ordained in 1936 at St Peter Missionary Baptist Church in Columbus. Georgia. He joined the army at Columbus’s Fort Benning, fought in the South Pacific, and returned to Columbus. (“I learned everything I know in Columbus, Georgia,” Reverend Dennis said when he learned that his visitor was born and raised there.) [Unless noted otherwise, all quotations by Margaret and H.D. Dennis are taken from interviews conducted by William Arnett in 1998.] Through the G.l. Bill, the Veterans Administration provided him with four years of trade schooling in the art of brick masonry, a skill first taught to him by German prisoners. They showed Dennis how to “do stuff hadn’t nobody else done in this world, do it different, and you can always tell it's your own work.” But he ended up spending twenty-three years in Detroit as an autoworker, building Chryslers and using none of his vision and creativity.

H.D. Dennis is Margaret Rogers’s second husband. Referring to her first husband (of thirty-nine years), she says, “He went to the South Pacific also, to fight, and come back without a scratch, and then one day robbers come in the grocery store and killed him. Then she met the Reverend. “He asked me would I marry him,” she explains. “I wasn’t exactly sure. But he said, ‘If you’ll marry me, I’ll turn your little old brown plank store into a palace.’”

They married in 1984, and the Reverend’s “palace” became a promise kept. It started with one tower. If and when this tower is completed, it is intended to house his re-creations of the two tablets of the Ten Commandments, which he has been holding for that purpose Meanwhile, the tablets are accommodated by the elaborate sacred Ark of the Covenant, made by Dennis from a steamer trunk, lots of costume jewelry and gold paint, several locks, protective satin cushioning, and, among other things, a glass doorknob “that got the All-Seeing Eye. I’m talking from Masons now, four thousand years. I learned it when I was young. It’ll take you a long way.” Dennis has taken himself a long way. When he unleashed his imagination and energy, and his ambition to employ in full his masonry skills learned many decades earlier, Dennis did not realize where he was heading. The place just kept growing, and Dennis’s ambition and his vision grew with it. People try to describe it. Several have written of its resemblance to a red, white, and blue Lego fortress. One journalist ventured, “If architecture is frozen music, this is a southern gospel choir singing in a Delta blues juke joint.” Or perhaps a postmodern medieval necropolis designed by a Tuscan Hindu architect. Sometimes a place defies sober description.

Reverend Dennis and Margaret Rogers Dennis enthusiastically welcome guests, tourists, and all strangers. “Come on in, come in,” Dennis shouts and gestures to anyone who stops to look. “They Come here from everywhere in the United States and fourteen foreign countries,” he proudly says. “I had Russians and a lot of Japanese people come here. I am an inspired man of God for people all over the world. You won’t find this nowhere else in the world, because God gave me the vision to do it just like this.”

The Reverend’s architectural assembly continues to evolve and mutate; it will probably never truly be finished. The octogenarian Dennis’s physical strength is diminishing, his eyesight is failing, and his hearing is all but gone. And there are other obstacles. As Reported in the Clarion-Ledger, a Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper,

He considers the store a work-in-progress, but modern building codes have put a kink in his plans. After the neighborhood around Margaret’s Grocery was annexed three years ago, Vicksburg officials refused to issue Dennis a permit so he could finish a shaky-looking, two-story tower on the store’s north end.

“I want to make an Upper Room so sinners from Jackson can come over here and pray,” Dennis said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen now. I still want to build it. I answer to God, not the city.”

Vicksburg code inspector Ed Partridge said he couldn’t issue a permit because Dennis did not submit building plans. Dennis must prove his prayer tower would be safe to occupy.

“Rev. Dennis told me God told him to build a monument, and that what he’s doing” Partridge said. “I don’t know about that. I really think God would have told him to get some plans if he wants to make one.”

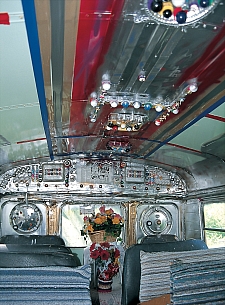

Beneath the Ten Commandments of God tower, with its unfinished Upper Room, is an old school bus in a new incarnation. “It’s a bus on the outside and God’s place in the inside,” Dennis tells his visitor as they enter the bus, now transformed into Reverend Dennis’s church.

The bus is not like your average bus or average church, either. It is heavily decorated with beads, found materials, artificial flowers, hubcaps, aluminum pie plates, light bulbs, lots of gold and silver and red and blue paint, some biblical art reproductions, and much more, covering the ceiling and all the walls. Nothing is left unadorned except the bus seats, which serve as comfortable pews. At the front of the church, on the driver’s side, is the pulpit, behind which the windshield has become an exotic high altar. At the rear is another altar, elegant, uncharacteristically restrained, more serene than its front-of-the-bus counterpart. This place could be, well, a place of worship built by Oriental magicians for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Reverend Dennis comes about his nickname “Preacher” honestly. Preaching is what he does, practically all he does. And though he punctuates his sermon-like conversations with such phrases as “Glory hallelujah” and “in the name of Jesus Christ,” his approach is that of a social and political historian and critic. He will start with an ordinary theological statement (he is, after all, Preacher Dennis), such as “God made you to worship him” but he will then sneak into the real message on his mind: “And God gave us this country three hundred years ago”—and he will look at his audience, stare at it, gesture with his hand, then move the soliloquy forward—"and God gave us this country and his blessings so Christians could come here from the old country to escape their persecutions”—and he will look away, and then back, as anger enters his voice and he delivers his punch line ”and we done more dirty work in three hundred years than they done in the old country in six thousand. Hallelujah! Tell them I say that, Reverend H.D. Dennis, Vicksburg, Mississippi, inspired man from God. There is not another one like me.”

Dennis moves comfortably down the aisle, between the pulpit and the rear altar, talking, preaching as he goes, and then suddenly turns and faces the front. He raises a hand and starts to speak of the ancient Israelites, but by now the audience suspects that he is being allegorical. He begins in an even voice, like a Sunday school teacher: “The children of Israel broke every covenant, every vow they made with God, and every time they broke it God put them in slavery for a thousand years, and they be saying to God every time, ‘Let us out, God, we won’t do it no more,’ and God let them out and they went to breaking it again. We’re like that right here in America. We got God’s blessing but we don’t keep the vows.”

Next, he calmly, matter-of-factly informs us, “I am a man of God and I must keep my vows. You can’t tell a man what to do when you ain’t doing it.”

He is not nearly finished. The duration of his sermon is determined only by his audience’s time constraints. “God is in a fight, a fight with the devil for people’s spirit. We got crime. Every day we got crime to show the devil’s influence. Money ain’t going to stop that crime. The government spend money, expect to stop crime, build more jails, millions of dollars to every state for building penitentiaries. That don’t stop the crime—the robbing, the drugs, the killing. Hire more police? You know what the devil do? He hire more demons.”

He then moves in on his conclusion, his solution: “We’re just pretending in this country. You got to let Washington, D.C., know. They got to know. You got to tell them, tell them we just pretending. We ain’t what we supposed to be. We ain’t keeping the vows. We got to get together in a united church in America and we can stop crime and we can beat the devil. A house divided will not stand. Races divided will not stand.”

He adds his assertive verbal signature, like an artist who wants his every work to be convincingly signed and recognized: “And you tell them in Washington, D.C., that this message come from Reverend H.D. Dennis, spirit advisor for the world, chosen by God from the Creation six thousand years ago.”

Finally, Dennis becomes philosophical, poetic, and emphatic: “Let people know why we’re all different colors. It is a bouquet. We is all a bouquet for God. Everything God made—trees, automobiles, flowers, everything that lives—is different colors of God’s bouquet. We make a beautiful bouquet of colors with our different shades of skin. God make it beautiful. . .” His voice tapers off. But to make sure we don’t leave the church too confident of our better natures, he attaches an admonition, emphasizing each word, ". . . and we abuse it.”

As befits the environs of a church (no matter that it is an unconventional church), there are painted signs everywhere. One of them, atop the Ten Commandments tower and repeated three times elsewhere, admonishes: “St. Matthew 21:13. It Is Written My House Shall Be Called The House Of Prayer But Ye Have Made It A Den Of Thieves.”

Another tower is surmounted by a plow’s harness and bears good news: “The Devil Is On The Run.”

Atop and beside the grocery store are signs providing more mundane information: “Bible Class On Weekends”; “The Best Bible Teacher Is Here”; The House Of Prayer Is Open Today”; and the ecumenical message above the door to the store, “All Is Welcome Jews And Gentiles Here At Margaret’s Gro. And Mkt. And Bible Class,” a sentiment that is abridged on a sign on the bus/church windshield to read, “You Welcome Jews And Gentiles.”

Walking around the maze of structures in front of Margaret’s Grocery prompts, for devotees of architecture, a mind-boggling deja vu. Don t look too closely, block out the colors, and you might imagine the campanile of the Duomo in Florence, designed by Giotto in the fourteenth century; and the gates of the two-thousand-year-old Buddhist Great Stupa at Sanchi, in central India; and the New Orleans tomb of a voodoo priestess; or an early Brancusi—all overlaid with contributions by Kurt Schwitters and Howard Finster and Piet Mondrian. It is like the multi-towered Tuscan town of San Gimignano, if it were to be wrapped by Christo in fabrics designed by Mississippi quilter Sara Mary Taylor. Or, and perhaps more aptly, it is something that Frank Lloyd Wright—or Herman Don Dennis—might have made if he had been given a set of giant Legos.

Like any master architect, H.D. Dennis has by now conceived his compound in its totality, and though at first glance it may appear to be spontaneous or even arbitrary, it is, like most of the best African American vernacular art, a careful ordering of chaos. Many of the towers exist in pairs, sometimes side by side or flanking a walkway or another structure (a pair of columns, for example, surmounted by plaster eagles, on the north and south ends of the store). Individual towers, or gates, or monuments, or architectural eccentricities, all relate to each other; they are joined, and balanced, by pathways, walls, fences, and other elements, colors coordinated, forming a surprisingly unified grouping. They are also joined and balanced by theme, philosophy, and purpose: social criticism over here, social criticism over there; anecdotal message back that way, anecdotal message up this way; idiosyncratic cruciform tower facing north-south, idiosyncratic cruciform tower facing east-west. Quotation from Matthew on that side and this side, and up there and down here. (Given the fate of Margaret Dennis’s first husband, the Reverend surely intends these Gospel words to remind would-be intruders that this is sanctified ground.) Also, in his arrangements of materials (almost always bricks and cinder blocks) and colors (almost always red and white), Dennis is in tune with the improvisation, syncopation, and intellectual spontaneity of African American cultural expression: predictable, predictable, predictable, predictable, unpredictable (e.g., one, two, three, four, seventeen). (You never know what is coming next, but the artists do, and somehow the best of them usually seem to get it just right.)

Across from the entrance to the bus/church is one of what might be called Dennis’s “proverb towers.” A simple column of cinder blocks, painted red and white, is crowned by a welder’s mask painted blue and white. It represents another slice of Dennis’s theological/philosophical wisdom. “It is a symbol of a knight,” he says, “like the ones that sit at the Round Table. It is a symbol of salvation. When knights went out, they put the veil down over their face, so couldn’t nobody know them. When they return to the camp, they lift the veil up. They got to let their camp people know who they is at the Round Table. God know who you is.”

The centerpiece of the complex, the tower closest to the road, is a black structure on a base formed by a star-shaped wall. On three sides it proclaims, in vertical letters, “God Love You.” The body of the tower is dressed with mirrors, reflectors, plastic strips, and various embedded objects. On top is an assemblage of circles, hearts, and spheres, interrupted by parallel vertical rods, which themselves are dissected by a horizontal rod. It is an enigmatic crown to the most uncomplicated statement. This stationary sculptural crown resembles an automated constellation in a science museum, one that describes the interacting components of the solar system. It seems only the flick of an “on” switch away from perpetual gyroscopic movement. God is not in the machine, God is the machine.

Along with the horizontal one, the two vertical rods form a pair of crosses that together resemble a football goal. The highest component of the tower looks like a broken basketball goal. On two of the shorter towers constituting this monument are some found objects combined to represent lamps, containing Olympic-like flames. Dennis loves to hide messages. Perhaps this one is that God surely loves you, but he will decide the outcome of your games as he sees fit.

Visitors parking directly in front of Margaret’s Grocery will enter the building by passing through the archway of an imposing structure of bricks and cinder blocks painted red and white with blue trim (and a few touches of yellow). This tower is as close as Dennis’s vision comes to seeking architectural symmetry. The tower, probably inspired by some combination of church facades, quilts, prayer cloths, and the American flag, appears to attest to the architect’s patriotism, in addition to his always conspicuous religious beliefs.

On the street side of the tower is a professionally painted sign advertising “Margaret’s Grocery & Market, Home of the Double Eagle.” A wood cutout of a double-headed eagle crowns the tower, and another decorates its reverse side. Nearby, a tattered American flag flies from a pole embedded in a red, white, and blue concrete base.

But this is not John Philip Sousa’s double eagle, nor is it Francis Scott Key’s flag. “Double-headed” could be interpreted as “two-faced,” and while Dennis gives us a great monument to church and state as an entryway to his home and place of business, he presents a balanced evaluation of both institutions. He points out the strength in unity, but wants everyone to understand the weakness of discord.

Margaret Dennis has her own explanation for the double-headed eagle: “Caesar Augustus and his brother Josephus ancient rulers. One ruled East, one ruled West. Each one had the eagle as a symbol of his power. Caesar Augustus went to war, beat his brother, and put them two eagles back to back, called it a double-headed eagle. It meant that it was a great empire.”

In the center of the bricks that form the tower’s archway, Dennis has planted a keystone-shaped slab of concrete, referred to by Dennis as a “cornerstone.” Unlike its Roman prototype, this undersized keystone is not functional but is purely symbolic, placed there for its concealed message, revealed by Dennis as he points to the “stone”: “Thousands of years ago a stone was cut like that and rejected because it was not square. But Jesus is the cornerstone, the chief cornerstone, rejected back then, and his teachings still rejected. It got to be respected and accepted now. Americans got to return to the truth, got to obey the law.”

The letters B and J adorn the south and north sides of the arch, respectively. They stand for “Boaz” and “Jachin,” names given by King Solomon to the two pillars (south and north) in the vestibule of his temple.

Flanking the entrance to the grocery, on its porch, are vignettes that symbolically encapsulate Dennis’s theological convictions. To the right of the door are three white plastic chairs-thrones, emblematic of the Holy Trinity—above which are a star (the Eastern Star is the Masonic organization for women) and bull horns, together representing female and male. (These are probably autobiographical.) Then there are the Masonic insignia, appropriately on the shutters. (The flow of information can be controlled-opened or shut.) “True knowledge, it come from God; see that mark, a G—use that letter for God.” Dennis is sure of what he says. He then points to one of the features of the porch grouping. “See them bricks,” he says, referring to a silver-painted, partially built brick wall in front of the chairs. They are not bricks at all. Dennis has turned wooden blocks into perfect trompe loeil replicas of ceramic bricks. “Hasn’t nobody figured out yet they made of wood.” Perceptions are illusionary. God is the source. Masonry is the way.

At the other end of the porch, a single metal chair sits beneath another Masonic insignia. This green and black chair has a woven back and seat with the Masonic emblem. Behind, collaged to the window, are prints and posters depicting various modes of transportation: Freemasonry will take you where you want to go.

The grocery store, or whatever it really is, does not resemble a typical grocery store. For one thing, there are no groceries apparent. For another, the entire anteroom, of approximately ten feet by twenty feet, is decorated from floor to ceiling like the school bus/church (and then some). Everywhere there are clusters of beads, toys, photographs both biblical and autobiographical, posters, artificial flowers, Christmas-tree ornaments, newspaper articles, costume jewelry, and rippling strips of plastic, mostly red and white.

The room’s piece de resistance is the Ark of the Covenant, but there are other discrete objects to complement and compete with it. Nearby is an assemblage of the expected materials: artificial flowers, beads, costume jewelry, gold paint, and the rest. They form a heart on a pedestal. At the heart’s highest point is a light bulb with three candles on each side. It looks more like an ultra-Reform menorah, or a box of Valentine’s Day chocolates, than like a Christian icon. Dennis says it commemorates the “seven churches of Asia Minor” (those ubiquitous Oriental magicians again), and when the Ark of the Covenant is closed, and the tablets of the Ten Commandments stored away, the Seven Churches sculpture stands on the Ark’s lid.

Hanging nearby is a large heart of red plastic tubing, within which is a smaller white heart, completely encased in beads. Purple beads (heart blood?) hang from the red heart. Attached is a yellow sunflower (sunflower = sun = God = life = eternal life), one of the most widely found symbolic objects in rural African American yards and houses. Dennis calls this piece Let Not Your Heart Be Troubled, and explains, “The big heart pump blood, keep you alive, but the white heart is the spirit-heart. You got to be born again with the spirit-heart: Jesus Christ!”

Hanging next to the heart is a companion piece that consists of a wreath-like circle surrounding a smaller one, both or them heavily wrapped with multicolored beads and glass balls. “Ezekiel” is how Dennis identifies it. “Faith and grace. Big wheel turn by faith, little wheel turn by grace. Glory hallelujah!”

As of this writing, the Dennises are both in their eighties. The city of Vicksburg lovingly restores and preserves its many antebellum houses, but has offered no plan to do any such things for Margaret’s Grocery and the Reverend’s one-of-a-kind sculptural/architectural garden. It is located at 4535 North Washington Street, so visit it if you can, as soon as you can, because this place earns three stars.