Robert Howell

About

Robert Howell is the youngest of eight children born to Charlie Howell, a paper mill worker, and his wife, Bessie. He was born around 1934 but says he cannot be certain about the year because there are no birth records. He still lives where he came into the world, on a country road in Powhatan County, Virginia, only a dozen or so miles from Richmond. “On the very same spot,” he emphasizes. “Right here.”

The fourth grade in Powhatan’s school system was Howell’s last:

“I had to go to five different schools by the time I hit the fourth grade. That’s the way they done us back in them days. Wasn’t nobody interested in educating little colored children. We walk, too. That was before school buses. They wanted us to do something, but not learning no lessons. They punished you in them days if you don’t do it right. We walk to school, carrying that book, carry a apple, kept our mouth shut. You know what I done every day at school? Put bottoms in chairs.”

He dropped out of school and worked in the local sawmill for about five years. Then he apprenticed himself to a local plumber for about eight years—”pretty good years”—until he found a better job. A white man named Mr. Blue, the owner of a nearby lake, hired Howell to be its caretaker. Howell’s job required him to “cut the grassland wash shrubbery around the pond. I done it for about five years.”

Charlie Howell owned two small stores on his property. When Robert and an older brother were teenagers, their father gave each of them a store to run to supplement their incomes. Robert sold “candy, pop, cookies, the kind of stuff whatever kids is looking for.” His older brothers bought him a station wagon that same year. (As the baby of the family, young Robert received much attention.) Deciding that he was not cut out to drive a car, he parked the station wagon in a big field behind his house, and the vehicle never moved again. Later he was given a Pontiac by one of his brothers. It went to the same field. When that brother eventually came back to visit Howell, he discovered that the tires had gone flat. The brother replaced the tires and urged Howell to learn to drive. The Pontiac has not moved. The next gift from a sibling was a pickup truck. Same result: it went straight to the field and was never used.

“I couldn’t see myself in no car” Howell explains. “Listen, I got something like fifty bicycles around here. If I want to go someplace, a bicycle will do me fine.”

Holding a conversation with Howell is akin to sitting in the congregation of a fire-and-brimstone preacher who occasionally permits listeners’ responses. Hardly a sentence departs his lips without at least a word or two being shouted—not always the word one would predict. A visitor might assume this artist is filled with some equivalent degree of stridency, but if there is any anger inside him, it remains deeply concealed, emerging only in an occasional recollection, such as his memories of school.

When he has an opinion, however, he invariably communicates it with emphasis; conversely, with a corresponding lack of concern, he concedes those things he doesn’t know. Once, while describing his art, Howell referred in passing to his father’s having had only one arm. When the interviewer asked about the missing limb, Robert says he never asked about it so has no idea what happened to it. What doesn’t concern him, doesn’t concern him. That untroubled aspect of his personality expresses itself in his art as much as in his life:

“I’m right, man. I got everything. I like to be outdoors. I like to be by myself. I don’t stay inside much. I can’t watch the hateful stuff they ram down your throat on television—killing and violence. Hey, I don’t visit nobody. I don’t want to go nowhere. I don’t even call my kinfolk. There ain’t nobody I want to listen to no more. You know, old folks used to tell me stuff back then, and back then peoples listen to old folks, and that stuff stay in my head to this day. Stuff peoples talk about today go right on by.”

Between Howell’s young and adult lives, he spent three years “pitching potatoes” in Long Island. Eventually he “had enough of that stuff and returned home—”came right hack here”—to work at Sears.

“I stayed there eight years, and what’d I do? Put up chain-link fences. OK job, OK money man. Then I went over to the place they call the Tuckahoe Condominiums in Richmond. You know about that? I stayed there, oh, about sixteen years. It’s a place for old folks to live, but not poor folks. Them peoples living there got some right-smart money, boy It is one high-class retirement home, Bud. I was there sixteen years. Quit working about eight years ago. Had enough."

Making art came later:

“Now, I hadn’t given too much mind to that kind of stuff. Wasn’t till I was working at Sears. Roebuck that the mood hit me. I was at a hardware store in Richmond, see, and I was looking at this thing. Couldn’t stop staring at it. It was this duck, a whirligig duck My supervisor; Mr Lawson, was with me, and he kept telling me, ‘You better buy that duck, Robert, the way you looking at it.’ I said. ‘No, I think I can make that thing myself.’ I went right on home and made me a whirligig duck man. Made me one. I was so happy about that thing, and it worked. It worked itself a long time. Man, I’d watch that thing out of the window, and it’d be flying. Wind blow, that thing go. See, I don’t just make it and leave it alone. I investigate my stuff. I be studying my stuff, see how it work, how to make it better I imagine that was about thirty-five years ago. Seems like about the time the Kennedys was being killed.

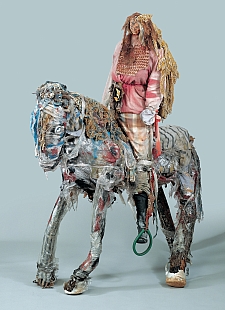

"I made whirligigs for a while. Got tired of that and started thinking about what else could I do. So I made me a flower girl that was I guess you could call my first piece of art. That thing stood out there for so long, but it got so ‘lapidated, worse and worse. We got a bad wind blow out here. Man, that wind come whip through here like ain’t nothing you ever see. That wind pick them things up and turn them over. After that I made me that zebra out there, or . . . what you call that thing? . . . oh yeah, giraffe. It used to fall down all the time but I got that stob in there and ain’t had no trouble in forty years with it. Then I made me a Statue of Liberty, and it fell down a heap of times from the wind, and I had to haul it out. That elephant out there, it came next. Built it out of cedar and a fifty-five-gallon barrel. It still out there but going down. Man on a horse after that. It fell down. That bull still standing. Lost his eye but I’m going to fix it.

"So I went to making all this stuff for myself. Some big things and then little things. The yard come to get to filling up, and I didn’t have no idea nobody would be wanting any of this junk. But peoples started coming over here saying, ‘You sell me this? Can I buy that?’ They buying stuff like crazy, and I couldn’t keep them small kind of piece.”

Howell’s problems, as he sees them, are minor. Although he has placed artworks near a busy farm road, he doesn’t even worry about theft. “They ain’t going to take nothing, buddy. I got a dead-eye dick in that house don’t promise you nothing out in that road.” (Approximate translation: I have a serious shotgun inside and can hit anything at a distance.) Besides, his homemade burglar alarm is rigged up in a tree near his house, so he generally sleeps soundly.

Cooking is his second love. His beliefs, personality, and techniques apply equally to his kitchen and his workshop:

“I can make anything out of anything. My cooking don’t quit. I can work over a plain piece of lettuce and turn it into something knock you out. I don’t eat like most folks around Here. But I eat good, I tell you. I don’t like them grits too much, but I love my rice, Bubba. I’m funny about water. I can’t handle none of it; straight; can’t stand it by itself: make me sickified. Powhatan got the best water in the world, man, but I can’t drink none of that stuff, though. Got to put something with it. Maybe make ice tea out of it, or mix up my own orange juice. Oh yeah, I can get my water a-many different ways”

He admits sometimes encountering a genuine quandary, such as deciding what color to paint some wooden pumpkins he has made for Halloween decor: “I had a heap of trouble with them pumpkins. Man, a pumpkin ain’t yellow and it ain’t orange and it ain’t pink. It’s a damn strange-colored sucker. But, man, I told you I study stuff, and I made me a color after ‘while that suited them pumpkins.”

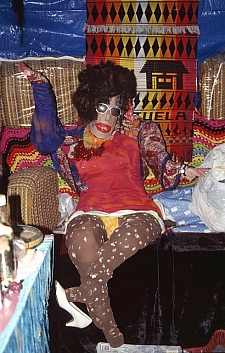

Pumpkins are naturally strange fruits, but Howell’s pumpkins are beyond pumpkin strange. His are seemingly too plump, too chiseled, and too colorful, as if Howell were testing the theoretical limits of the truism that art must be greater than the sum of its parts. Can there be an “art” part when the volume is already turned up to its highest for every aspect of the craft (line, color, mass, texture)? Too much, of everything or of anything, is usually aesthetically counterproductive; however, Howell’s rococo rawness, his flip funk, is not far off the ritualized competitions of black American life: school children playing the dozens, breakdancers calling out each other to ever more impressively athletic moves. Howell’s pieces are entrants in a slam-dunk contest.

Analyzing his art much further is a bit like speculating why his father had just a single arm: There has to be an interesting story there, but Robert Howell isn’t going to offer many clues. This much is certain: He doesn’t care to reinvent genres. Despite his footloose style, his roots are in “conservative,” countrified art, standard yard stuff mainly whirligigs, birdhouses, weather vanes, and gazebos—examples of which he might have been able to see that first day at the hardware store. Art animals have grazed and loped throughout the property since his earliest days as an artmaker. One of his oldest works, for example, the Statue of Liberty, falls into a sui generis category of American whirligig displays—and American folk art in general. Whirligig flocks are still plentiful along many Southern byways (and probably elsewhere), but Howell hollows out such categories and makes them his alone. One gargantuan whirligig, a static weather vane, a Calderesque mobile on a grandiosely Calderesque scale, seems to blow back against the elements. Only a hurricane (or those strong Virginia winds Howell describes) could activate the vane’s unyielding appendages. Similarly, a gale—maybe—could have plucked the pipes of Howell’s giant wind-chime sculpture (no longer extant), with its rusting, empty helium or oxygen tanks hanging around, awaiting improbable breezes. The “church wind-chime” was as big as a cathedral’s pipe organ; Howell remembers that people “could hear that thing ringing miles.” This is art as cosmic smirk, mocking and celebrating that desire of Howell’s, and of all the rest of us, to play with nature.

Quotations by Robert Howell are taken from interviews conducted by William Arnett in 1997 and 1998.