Ronald Lockett

About

Until his death in 1998 from AIDS-related pneumonia, Ronald Lockett was the youngest noteworthy southern African American visual artist and one of the few in his tradition to possess no personal memories of the civil rights movement or the coarsely segregated social climate that preceded it. Throughout his life, Lockett was intensely self-conscious of the odds against him, of his membership in that most lost of recent American generations—inner-city black males—whose loudest cultural sign is the fear they provoke throughout American society. The art he left stands at a little-documented historical crossroads between two generations: between, on the one hand, a world of his African American fixed in their declining community, its ghosts whispering about prior times, and on the other, the world of late-twentieth-century urban black youth and the television. He lived after the great midcentury social struggles were over, when all the big issues had, to him, seemingly already been fought for and decided. His art would consequently be haunted by a quest to locate historical moorings for an existence he believed doomed or trapped. His accomplishment, ultimately, was to have wrought things personal and tough from the rumors, stereotypes, hunches, half-heard reminiscences, and television broadcasts through which he experienced history and meaning.

Death’s siege of life tormented him. His art was death driven, a convergence of his personality, physiology, family, community, ethnicity, and finally, his contracting of a disease he equated with immortal Death. At least in his art, something rejuvenating emerged from his simultaneous sensing of his social death as a black male, the decay of his community and the occupations that sustained his ancestors, the evaporation of shared memories and experiences as ties to the past, the horrors of extinctions and genocides, his nuclear family’s dissolution, his sexual frustrations and fears, and HIV.

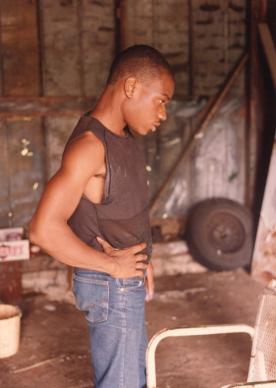

Prophesying his life, Lockett's art seemed from the outset to tell a story attuned to his world's ultimate collapse, which ended at the place—premature, unhappy death—he had always feared. He came from one of those dysfunctional families such as Tolstoy might have had in mind when he quipped that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Born in 1965, he lived all his life in the Pipe Shop neighborhood of Bessemer, Alabama. To outside appearances—always deceiving—his life was uneventful, almost unlived. Most of his hours will remain forever unaccounted. He graduated from high school but never took nor sought a traditional job. He learned no trade. One of a family of four brothers and a sister, Ronald lived in his mother's house his whole life, while two brothers left home to join the army or law enforcement, and the youngest brother all but left for the dangerous times of trouble with the law. Ronald's father, known as "Short" or "Little Bud," had split with Ronald's mother, Betty, when the artist was young, and settled with another woman in Pipe Shop. Betty suffered at least two breakdowns and finally became reclusive. She stayed home almost continually, until she moved to Texas to live with her daughter a few years before Ronald's death.

Although he seldom strayed from Pipe Shop, he was ill-suited to life in Bessemer. He was physically slight, possessing none of the toughness that is demanded of Pipe Shop's steel factory workers and that pumps up local conceptions of masculinity and virility. He punched around the neighborhood after high-school graduation, spending much time helping his relatives the Dials in their various concerns. Having no occupation or trade made him an anomaly—not because he was unemployed, but because he had no traditional ambitions whatsoever. (Since elementary school, Ronald knew he wanted to be an artist, and by the time he was in his early twenties he would call himself one.) Articulate but usually shy and uncomfortable in conversations, with a quietness some would consider furtiveness, depressive, at times enervated, and intensely self-analytical, Lockett was not cool by the standards of the streets or the mills. Ronald's "aunt" and former neighbor, Clara Dial, pinpoints his position in Pipe Shop: "Most folks paid him no mind."

Birmingham, Alabama, has become the Black Belt's own Rust Belt; and Birmingham's principal satellite, Bessemer, is a place where steel dependence muddles on, doling out hard times to residents whose parents and grandparents migrated from cotton fields to work in mines and mills. Many Bessemerites, surely, descend from the (mostly black) convicts impressed until the 1920s to toil in the area's furnaces as a price subsidy for local industry and a buffer against organized labor. Bessemer is a place founded to do almost as dirty a job as the plantations once performed. Still, despite its heavy industry, Bessemer remains a genetically Deep South kind of town, with a church or two gracing every four-way stop, and with hormonal attachments to stock-car racing and college football (the University of Alabama is a few dozen miles down I-20/59).

The human dramas of Pipe Shop play out before a large chorus of out-of-work, forced retirees—men in their forties through eighties, obsolesced by Pipe Shop's economic misfortunes or their physical inability to continue with the labor-intensive jobs available. These men are fixtures in the community, convening at its cafes and joints, and many of them frequently assembled on the elder Dial's porch a few doors down from the Locketts. Ronald was a ubiquitous extra, drinking in the tales, jokes, asides, wisdom, and recollections.

Closer still to Ronald were two family links to bygone black life. Thornton Dial and Sarah "Auntie" Dial Lockett (c. 1890-1995) loomed as steel-willed survivors of Jim Crow and memory bridges to the nineteenth century. Their examples nurtured and dwarfed his sense of the stakes of his existence. Thornton Dial, a lifelong creator of "things," didn't label his stuff "art" in the mid-1980s, but was almost always working on projects behind his home three houses away from Lockett. Lockett probably considered Dial an artist before Dial did, and Dial, one of the few adults who paid Lockett any serious attention, became a mentor to him. Ronald's neighbor and great-grandmother, Sarah Lockett raised three generations of Locketts and Dials, including Thornton Dial, and was still lucid and vibrant until after her one-hundredth year. Her mother wit shaped many Dial and Lockett men.

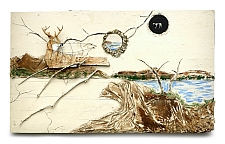

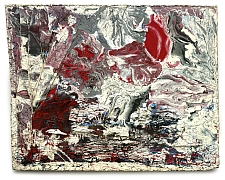

He learned to paint by watching Dial and watching TV, especially those kitsch-laden how-to-paint shows that teach formulaic, motel-art landscape and still-life techniques. In contrast, from watching Dial he picked up an approach to paint that treated the issue of representation as a problem to be attacked by any means necessary—in two dimensions or three, with any materials on hand. His early swirled compositions are Dial influenced but betray an underlying sense of conventional landscape, as in Poison River.

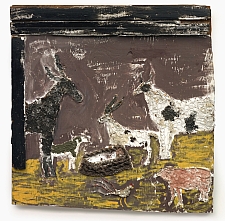

Despite the stylistic influences of the Western painting tradition, his art could hardly be more vernacular, for in at least five crucial ways he reconfigured traditional African American beliefs and practices. First, he used animals as the protagonists in his allegories in a manner that recontextualizes but is consistent with the roles of animals in nineteenth-century trickster tales and fables. Second, he used African American conjurational materials—blackness, rust, wire, poison, smoke—as the theme or physical medium for his works. Third, his preoccupation with instances of psychological transformation reflected a broadly vernacular emphasis on cathartic and ecstatic religious and performance rituals. Fourth, he was intensely concerned with eschatology—last or final things: a foundation of Afro-Christian theology. Fifth, he partook of the hermeneutic approaches of the root sculptor or the preacher, both of which seek prophetic signs in the found nature of a text—whether that text be the earth or the Bible—as a starting point for the communication of wisdom to others.

Wholly a vernacular artist, he was also a postmodern one; his life and art epitomize generational and aesthetic shifts. True to his times, he made pastiches of the local and the global, freely mixing artistic vocabularies and influences gleaned from disparate sources, ranging from those most at hand (family histories and lore, street talk) to those almost universally shared—primarily the influence of TV. His skepticism about grand Enlightenment notions—Creativity, Originality, Progress, the New, and so on—ultimately propelled him away from painting and toward collage. He struggled to come to grips with the meaning of history, even though the past was mostly just a quality of "pastness" to him—a style without narrative structure, a story of hints he never could quite weave together in his mind. But he wanted that pastness with all he had.

Has anyone else owned a cultural education so dominated, simultaneously, by African American folklore and cable television?

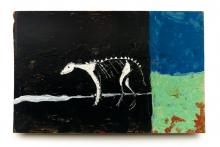

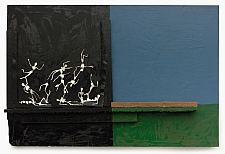

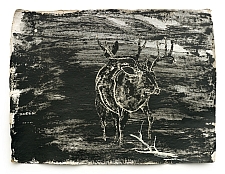

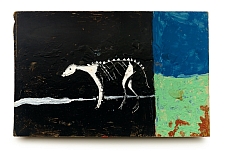

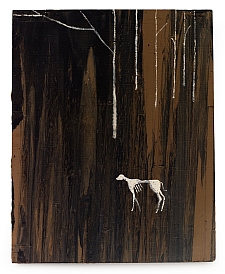

Rebirth, created when the artist was twenty-two, remains a gateway into all his subsequent artistic thinking. In the work, a quadruped skeleton ("a baby," Lockett called it), a matrix of wire and nails, exits a blue and green zone at right and moves into a black emptiness engulfing most of the picture. Rebirth turns away from the aesthetics of "life": (1) the colors blue and green, the basic indicators for water, air, chlorophyll; (2) adulthood—the movements all life makes toward biological maturity; and (3) right-sidedness, with its deeply set implications of left-to-right progress, literacy, timelines, evolutionary charts, rights-of-way, and etiquette.

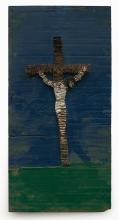

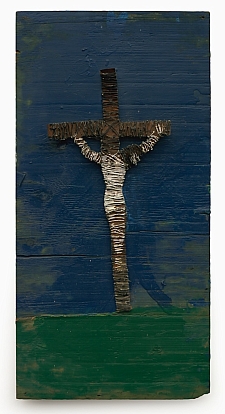

Rebirth relates to Sacrifice, a crucifixion of wrapped wire on a blue and green field, whose body of Christ is also fashioned of wire and nails. The skeleton of Rebirth investigates the liberating potential of nonlife. The animal moves backward through the picture, forsaking right for left, adulthood for youth, bigness for smallness, light for dark, terrestriality for absence. Rebirth announced Lockett's lifelong search, as fervid as religion, for new beginnings amid the nonlife of urban black male existence that had been his starting point in the world.

He was never a manic creator. His garage workshop was usually empty but for a work in progress and, situated about four feet away from the developing project, a chair, from whose perch Lockett would, sometimes for hours, inspect his developing picture. He often joked that he spent more time looking at his works than working on them, but his jest contained an important truth about his rare sensitivity to his own output.

Lockett's art sought to link momentous events with their humble residues. From the outset, these linkages operated through rhetorical tactics of indirection and through what has been called, apropos of African American culture, "obscuring the addressee" or "naming." With this strategy, Lockett frequently chose cataclysmic events of incontrovertible terror—the bombing of Hiroshima, the Holocaust, Ku Klux Klan violence—through which he pointed at contemporary African American suffering and his unseen life.

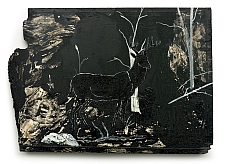

Lockett's most frequently used artistic metaphor, however, was white American overculture's like treatment of animals and non-white peoples:

When [white] people came [to America], they saw buffalo, and they exploited them, and they just destroyed them, because they could. They had guns; they just shot them down because they just could. They didn't really shoot them down because they had to feed theyselves; they shot them down just because they could It's wrong to destroy anything.

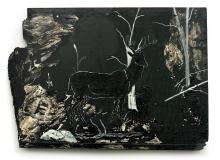

If works such as Hiroshima stir together history with Black experience, the confined deer of the "Traps" series conjoins the fate of the environment (an occasional deer still appears around the Bessemer mills) and the history of African Americans. History becomes a series of figuralisms; the fates of other peoples throughout Western history and the fates of ecosystems are the precursors of African American history.

Two of Lockett's brothers, for example, have been "trapped." His younger brother, Junior, has faced incarceration on and off since youth. Another brother, David, joined the army and left Pipe Shop. David became one of the few American ground troops taken prisoner by Iraq during the Persian Gulf War. (Instinct for Survival addresses David's disappearance.)

The effort Lockett put into making these deer fragile and graceful would later return as a belief in the enduring, if ineffectual, power of art, as in Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die. These animals' noble powerlessness proposes an added meaning—a sexual and reproductive one. An untitled elephant of 1988, with its well-endowed trunk, sketched the double entendres of Lockett's later animals-the musk ox, the wolf, the buffalo, as well as the antelope—which stood not just for masculinity, but as emasculated phallic symbols, their potency humbled and whipped towards extinction. This turn in Lockett's work was a signal moment in the postmodernization of the vernacular: the older, life-affirming animal symbols of folktales were transformed by him into "fresh" myths of decline, deracination, dilapidation, and impotence.

At least three forces (and then a fourth) were haunting Lockett. The first, as mentioned, was his artistic anxiety regarding his mentor, Thornton Dial. The second was his ambivalence about black cultural ideals of masculinity and his sense of the emptiness of such machismo, which he saw as at least partially a result of the commodification of the black body: black men had/have economic value according to their physique and strength, first in slavery days, continuing through subsequent roles as manual laborers for wage hire, and on down to the professional sports and entertainment industries of today. (Lockett's "body" had no value.) Third, the animals, especially the later ones from 1994 and after, take on added urgency in light of his life as an "endangered" species, whose mandate is to reproduce oneself. Endangered species must procreate, or vanish. He felt a quasi-political duty in the conservative black South to be a patriarch with a litter of little ones.

Fourth, his discovery of his HIV, sometime in 1994, convinced him that the boy without memory would pass away a man without legacy. HIV increased his general torment but at the same time clarified many of his deepest doubts. As his life fell apart, his work gained a clarity elsewhere missing; it took on a rage that his earlier work, though poignant, had lacked. The issues of marriage, of settling down, of having his own family, and his other perplexities about relationships became moot.

He kept his virus a secret from almost everyone, including many relatives. He had heard Pipe Shop whispers about his sexuality—which may have had more to do with his demeanor than anything else—and Lockett feared the branding and possible demonization that would follow his divulging of his condition. He believed he had contracted the disease from a girlfriend, who, in turn, he said blamed him for her HIV.

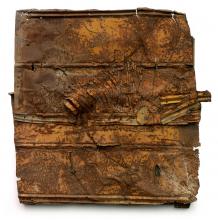

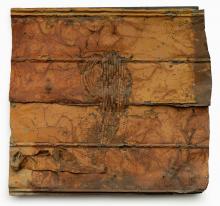

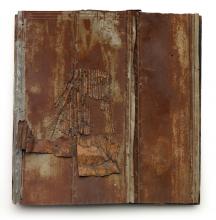

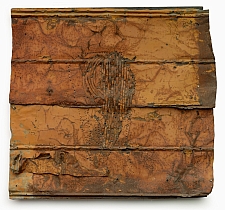

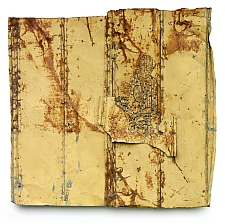

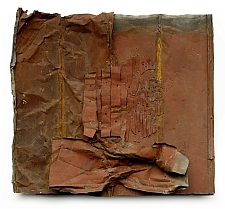

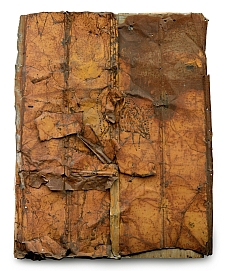

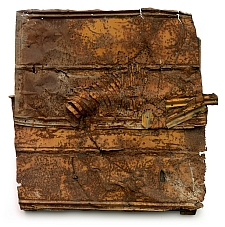

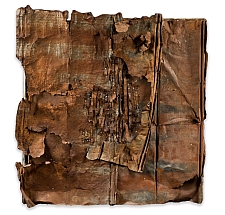

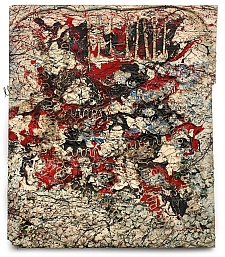

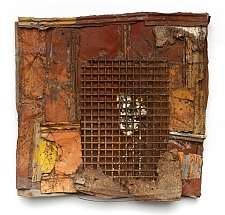

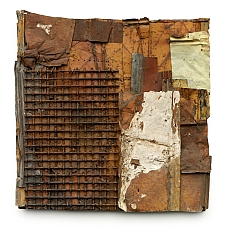

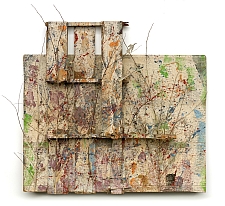

Shortly before becoming aware of his disease, he had essentially also renounced painting as a creative act, drifting in his technique toward works of tin collage, a more retrospective or curatorial attitude. In the early 1990s, he had discovered some weathered barnlike buildings once owned by the Dials, and he scavenged the rusty tin siding that had been covered with now oxidized paint by Thornton Dial in the 1950s and 1960s (before Lockett's birth). That old tin, the tough skin of black rural survival (and literally the roof over its head), as well as the oxidized paint brushed on it by Dial before Ronald's time, offered the younger artist his best means of translating feelings about a generalized sense of the past (including his mentor, Dial) into meaningful assertions of self. Decrepit outbuildings turned into broadcast towers for messages about former days whose memory-vessels—people such as Sarah Dial Lockett and Thornton Dial—were vanishing without replacement.

Rust and oxidation immediately became his voice. Thereafter, nearly everything is rusty, muddy, opaque—neither light nor dark, neither white nor black, but an in-between brown. In an earlier period, he had tackled the struggle between positive and negative forces in terms of the colors black and white (and occasionally red). Rust—the oxidized paint—resolved battles between light and dark, a dualism that had seesawed before in his work. Oxidation's color is that of earth or dirt, yet it isn't pure or originary, and it isn't final, either; it's a lengthy, almost endlessly transitory stage. The swirling opposites of earlier works, such as Poison River and Civil Rights Marchers, were folded together fully into the muddiness their entanglement augurs. He chucked his commitment to the myth of African American and human progress, his prior attachment to the universal opposition of right and wrong that powers black-and-white works such as Holocaust and Hiroshima. He took a sharp turn that his artistic father, Thornton Dial, would also take at the same time (with ridicule by TV's 60 Minutes, instead of HIV, providing Dial's catalyst), both men concluding that indeterminacy offered a more artistically productive belief system than certitude.

In tin, Lockett also found an unexpected source for the beauty he had always sought in his art. The autumnal colors and blotchy decay of the rust/paint (the rusty appearance is usually in fact weathered, iron-oxide-based paint) suggest continual rebirth. Each season has its beauty. These broken hues seemingly seek escape within or return to nature's cycles. Oxidizing paint is the artist, the chronicler of life, in decline—in decline as a cultural force and in decline as a scared Bessemer boy with HIV. This autumnal instant, of the tin's and paint's death and pending rebirth, is also the instant of the shock of death, that distant interiority of the expiring body, the glazed life force of the trapped prey species—the look of all Lockett's subjects, especially the trapped deer and other animals on the brink of extinction. The ultimate alchemical or homeopathic poison—death—blurs any remaining temporal divisions between life and nonlife. His rust/paint switches between decay and bloom, embedded between two successive layers or levels of time or existence.

The rust works may be read as attempts to excavate meanings from an obscure past or as attempts to lay away messages, facts and prophesies of self, for the future, in order to countermand his sense of sexual, reproductive, and historical barrenness. These two readings generate a third: that the rust works are both archeology and prophesy, whose holographic quality perfectly houses Lockett's image of himself—a fragmented, unrealized identity so spatially and temporally amorphous that it coheres only as a mirage, a scatter of tea leaves, a rumor, imprisoned dreams or stories that cannot tell themselves. There is seldom any narrative structure, only hints of events in progress—a gaunt animal stooped at a watering hole, for example.

And yet the topographic quality of these images, as textured as the earth, constantly returns their effect to the lived-in and the actual. They embodied the emotional and aesthetic struggle between the overwhelming tactility and the overwhelming virtuality of his experience of the world, a paradox true to his hypersensitive soul.

Tin brought together Lockett's two most consuming themes—traps and rebirth. Decaying tin records its story through an unpredictable twofold transformation. The process of decomposition leaves expanding necrotic emptinesses at the same time that it oxidizes, a chemical process that throws off exquisite dendrites. Rust, then, is a homeopathic material both eating its way backward into its support and blooming outward. The metal works become like geological strata or levels at an archaeological dig, where he salted away a prophetic archaeology, an archive for future excavation. His tin images are both trapped and reborn.

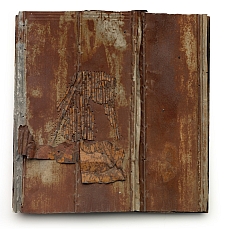

His early works confronted past tragedies by countering them with public "prosecution" or proclamation, with a veritable nostalgia for black-clothed evil (the Holocaust, KKK violence). His later tin composites use memory secondhandedly and obliquely; the figures flicker between representation, abstraction, and complete disappearance into their tin grounds.

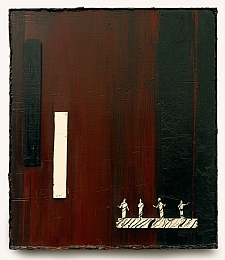

The Inferior Man That Proved Hitler Wrong is an homage to Jesse Owens that suggests the pent-up energy of an era of history—the black freedom struggle—is about to spring into full stride. Lockett's most compelling images were ones like Owens, whose position is a crouching animal (ready to strike at racism), a supplicant (using his humility as a source of strength) and a subject bowing or prostrating itself before a "master" (or "master race"). The submissively bowed athlete is anything but.

Fever Within, a paean to a friend who died of AIDS, mirrors Owens's crouch, but the figure is deflated, not crouching: Owens's race is history; the time lapsed was the era Lockett missed.

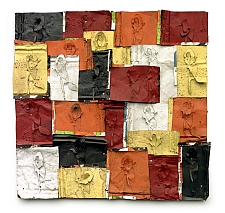

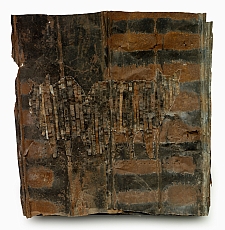

Around 1995, as Sarah Lockett's health began to fail, Ronald Lockett and Thornton Dial became increasingly interested in quilts. She had been a quilter, and now both men were beginning to sift through her effects. Many of her quilts, like the vast majority of African American quilts, were patternless improvisations of fabric blocks, more like quilt "backs" than stylized, formal patterns of quilt "fronts." Ronald began to consider the quilt a magic heirloom that tied together many generations in a shared language and process.

Also, at that time, existential bleakness finally overtook his work and life. Despair found meaning through outrage in a series of pieces occasioned by the Oklahoma City bombing of April 1995. Part city skylines and part shantytowns, these pieces shred the myths of the melting pot, the social mosaic, the American Experiment. Oklahoma, Timothy, April Nineteenth (The Number), Awakening, and The Enemy Amongst Us are frayed and tattered improvisational patchwork quilts.

Let us remain mindful, as Lockett was, that one of the dark motives for the Oklahoma bombing was white supremacy, that, far from being an act of maniacal desperation, the Oklahoma bombing was an intentional spectacle of terror, as lynchings once were. What lingers after the explosion is, as in the earliest work in the series, a nebulous cloud. Smoke? A ghost? A Klan-like specter? Will that ghost-cloud coalesce into a Rebirth also? The piece is also a portal, a gateway, or a window (prison window?) shrouding the white presence. (Recall the hazes of the black-and-white works.) Oklahoma is not Hiroshima, and Lockett knew it. The grand historical conflicts, and the communal sustenance they provided, have devolved imperceptibly, leaving this double millennium—the end of the Western world and the end of Black America as they have known themselves—to make halves whole by improvising in a new key.

In 1997 and 1998, he likely felt his health taking a bad direction. He intermittently suffered from what he shrugged off as "a cold" or "the flu," always maintaining that whatever was nagging him was unrelated to the HIV His artmaking became paralyzed by his gloom. During his final two years he was briefly artistically invigorated by the death of Princess Diana, in whose honor he made a series of valedictory, quiltlike works (England's Rose).

These also invoke the memory of Sarah Lockett, who had died in 1995 and had earlier been memorialized by him (Sarah Lockett's Roses). He made artistic peace with their deaths: Sarah's "natural causes," after a century of life; and Diana's precipitous accident, with the ensuing worldwide hagiographic adulation. Their deaths brought his ebbing life into stark relief. Their departures bore no resemblance to the one he saw in store for himself.

And the first physical sign of full-blown AIDS seems to have been the pneumonia that killed him in August 1998.

In excavating an evasive past, Ronald Lockett dug up lessons learned by modern anthropologists—the people who specialize in studying the likes of him. He found that he could not excavate whole, self-contained artifacts of an inorganic past, but could know the past only indirectly. Lockett's notion of history acknowledged that his subjectivity, his guesswork, was inseparable from what might really have happened. His intellectual crises were occasioned at least partly by his not having had the personal experiences of his elders—and his knowing he had not. As an artist, Ronald was finally reborn through his resignation to a permanent exile from communal memories. Fed a diet of historical junk food, he swallowed it and somehow thrived, wringing something individual and raw and wounded and alive from those romantic stereotypes and half-real reminiscences. His art began in despair and ended in tragedy, yet in the meantime, it explored areas that neither vernacular nor mainstream contemporary arts proper have, as a rule, been able to reach on their own.