Taking its title from folklorist William Ferris’s seminal text on Thomas’s work, The Devil and His Blues will be the first major institutional solo presentation of James ‘Son Ford’ Thomas’s sculpture to take place since the artist’s death in 1993. The exhibition will include 100 of his unfired clay objects in addition to two documentary films on his work: ‘Sonny Ford:’ Delta Artist, made by William Ferris in Leland, Mississippi in 1969 and JAMES ‘SON FORD’ THOMAS: ARTIST made by filmmakers Jeffrey Wolf and Zach Wolf, using footage shot of Thomas in 1982 while exhibiting his work as part of the seminal touring exhibition Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980, which has been edited on the occasion of this exhibition.

Widely celebrated as a major figure in the evolution of the Delta style of blues music, James ‘Son Ford’ Thomas was born near Eden Mississippi in 1926, later moving to Leland, Mississippi, where he lived with his wife and children from 1961-1993. His formative years were spent frequenting the rural house parties known as ‘jook joints,’ where locals would spend their weekends listening to blues music, dancing, drinking, and gambling. The traveling musicians he was exposed to as a teenager, notably Elmore James and his bottleneck’ style of guitar playing, contributed greatly to his pursuit of music and the evolution of his unprecedented approach to songwriting and singing, which chronicled life in the Delta.

Widely celebrated as a major figure in the evolution of the Delta style of blues music, James ‘Son Ford’ Thomas was born near Eden Mississippi in 1926, later moving to Leland, Mississippi, where he lived with his wife and children from 1961-1993. His formative years were spent frequenting the rural house parties known as ‘jook joints,’ where locals would spend their weekends listening to blues music, dancing, drinking, and gambling. The traveling musicians he was exposed to as a teenager, notably Elmore James and his bottleneck’ style of guitar playing, contributed greatly to his pursuit of music and the evolution of his unprecedented approach to songwriting and singing, which chronicled life in the Delta.

Thomas’s uncle Joe Cooper taught him to play guitar beginning at the age of eight and also taught him to sculpt the local ‘gumbo’ clay, from which Thomas initially made his own toys, resembling dogs, horses, and the numerous Ford model tractors that earned him the local nickname ‘Ford.’ He chose to keep this name throughout his professional career as homage to the place from which he came.

Thomas made sculptures regularly throughout his adult life, creating hundreds of unfired clay pieces from a repertoire of subjects, many of which date back to his youth. His birds, snakes, squirrels, and fish are all representative of Delta wildlife in addition to holding symbolic significance in the African-American folk spirituality known as ‘hoodoo,’ in which he believed. The skulls for which Thomas became known were first made as a mischievous ten-year-old, with the purpose of scaring his grandfather. After a ten-year period working as a gravedigger, from 1961-71, Thomas began making skulls again, this time with the aim of accurately representing the dead, often using real human teeth or dentures and a dull white paint he created to simulate the look of bones. He deemed these works inappropriate for children, yet also intended that they be used as utilitarian objects including pencil holders and ashtrays. After his time working as a gravedigger, while reflecting on his sculpture and the topic of death, Thomas stated, ‘We all end up in the clay.’

Thomas made sculptures regularly throughout his adult life, creating hundreds of unfired clay pieces from a repertoire of subjects, many of which date back to his youth. His birds, snakes, squirrels, and fish are all representative of Delta wildlife in addition to holding symbolic significance in the African-American folk spirituality known as ‘hoodoo,’ in which he believed. The skulls for which Thomas became known were first made as a mischievous ten-year-old, with the purpose of scaring his grandfather. After a ten-year period working as a gravedigger, from 1961-71, Thomas began making skulls again, this time with the aim of accurately representing the dead, often using real human teeth or dentures and a dull white paint he created to simulate the look of bones. He deemed these works inappropriate for children, yet also intended that they be used as utilitarian objects including pencil holders and ashtrays. After his time working as a gravedigger, while reflecting on his sculpture and the topic of death, Thomas stated, ‘We all end up in the clay.’

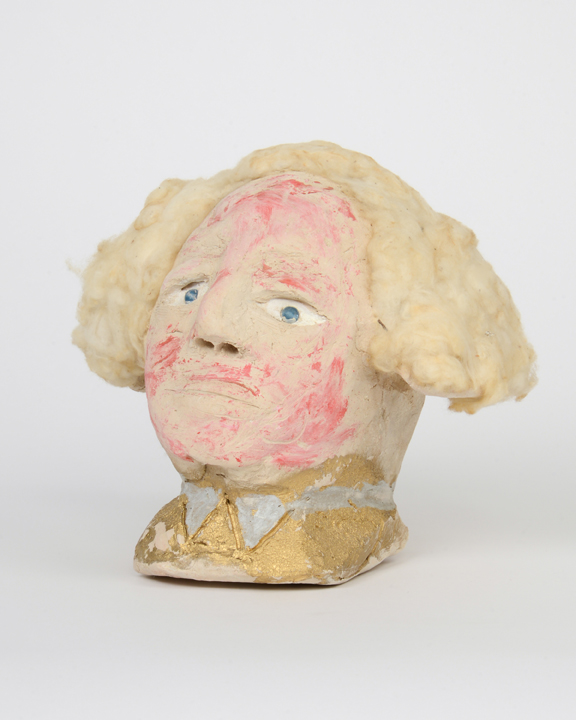

Numerous busts of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln were made in part for their general popularity and subsequent sales and yet they also speak to the history of slavery and its residual oppressive policies, which Thomas faced throughout his lifetime. The cotton wigs that he created for each Washington bust reflect Thomas’s own history with cotton, which he picked with his grandfather to earn a living as a young man. As an adult, Thomas grew cotton as a sharecropper, requiring that he rent the land and buy overpriced supplies from its white owner, incurring tremendous debt that made earning a living impossible. Thomas’s sculpted quails reference the local ban that was placed on the right of African Americans to hunt them. Due to their high meat content, quails were reserved as a delicacy for hunting and consumption by white people only.

Numerous busts of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln were made in part for their general popularity and subsequent sales and yet they also speak to the history of slavery and its residual oppressive policies, which Thomas faced throughout his lifetime. The cotton wigs that he created for each Washington bust reflect Thomas’s own history with cotton, which he picked with his grandfather to earn a living as a young man. As an adult, Thomas grew cotton as a sharecropper, requiring that he rent the land and buy overpriced supplies from its white owner, incurring tremendous debt that made earning a living impossible. Thomas’s sculpted quails reference the local ban that was placed on the right of African Americans to hunt them. Due to their high meat content, quails were reserved as a delicacy for hunting and consumption by white people only.

The bust portraits, which constitute the majority of Thomas’s creative output, portray numerous members of his community as well as imagined faces, often incorporating marbles as eyes, wigs, real human hair, found sunglasses, and jewelry that he fashioned as he became increasingly interested in the use of embellishments. Thomas also created a small number of miniature clay dioramas, often depicting full figures chopping wood, eating watermelon, playing music, or posed dead in coffins. These works reflect the scenes of daily life and death, which he observed.

Paradoxes of meaning and function are central to Thomas’s intent, imagination, and intuitive approach; the quotidian and the abject, beauty and ugliness, excess and austerity, significance and meaninglessness, commercial viability and histories of oppression, and documentation and spirituality often co-exist simultaneously in a given piece.

James ‘Son Ford’ Thomas: The Devil and His Blues seeks to consider the entirety of Thomas's output in music and visual art as a remarkable document of American history: an epic autobiographical narrative, connecting mortality, nature, community, spirituality, and the culture of the region in which he lived.