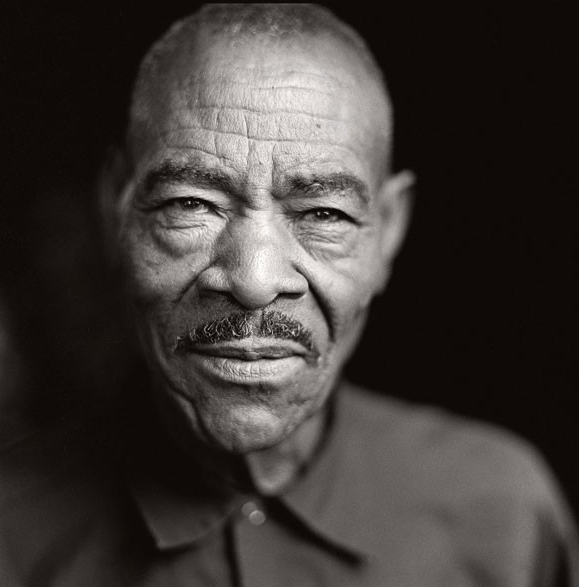

Thornton Dial, a self-taught painter and sculptor whose improbable life’s journey led him from a sharecropper’s shack in Alabama’s Black Belt to recognition by many of the world’s leading museums as a significant American artist, died at the age of 87 on January 25 at his home in McCalla, Alabama.

Dial’s art, by turns ferocious, witty, tender, and incisive, developed during many decades of complete obscurity, during which he created “things” clandestinely—unaware (as he explained later) of the Western concept of “art” as a special category of human activity. Due to apprehensions about how his socially critical and racially conscious work would be received, he broke apart and recycled much of his work as he went along. Only in 1987, at the age of 56, did he come to the attention of the art world and embark on an artistic career that lasted nearly thirty more years and brought him international renown.

In 2014, ten of Dial’s works were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a part of a larger donation from the William S. Arnett Collection of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. The Foundation was created by William S. Arnett to preserve and document African American vernacular art, including Dial’s work. In announcing that gift, Thomas M. Campbell, the museum’s director, described the work as “critical” to the museum’s commitment “to telling the story of art across all times and cultures.”

Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman of the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Museum, adds, “From the complex, exuberant textures of his assemblages to the deft, fluid lines of his drawings, Dial's facility as an artist was truly extraordinary. He leaves us with a body of work that is a rich visual manifestation of a life history, one that witnessed a remarkable time of change in the world from the perspective of an African-American man. In the sadness of his passing we realize that we've lost a deeply humane artist, one whose injunction to others will hold true for Dial himself: ‘If there is one thing that you can do, leave something for somebody else...You can work for somebody's else's freedom....This is life.’”

Thornton Dial was born in 1928 in rural Alabama, near the town of Emelle, to an unwed teenager, Mattie Bell, the child and grandchild of sharecroppers. He never knew his father. He received limited schooling, passing his childhood in the double bind of Great Depression poverty and Jim Crow segregation. In 1941, upon his mother’s marriage, he was sent to live with relatives in Bessemer, an industrial satellite of Birmingham. There he soon entered the workforce, in highway construction, brick loading, carpentry, pipe fitting, house painting, and metalworking, among others, before beginning long-term employment the Pullman-Standard Company, where he made boxcars until the plant closed in 1983.

In 1951 he married Clara Murrow, and in the years after built a home for them in the Bessemer neighborhood known as Pipe Shop, where other members of his extended family also lived. He and Clara had five children, one of whom, Patricia, suffered from cerebral palsy and became the focus of much of their lives for the next twenty-eight years. A man of boundless energy, Dial seldom relaxed after his long shifts at the factory. Behind his house, and in the rummaged-tin outbuildings on his property, he was constantly “making things” of all sorts of found materials, using the construction techniques he had picked up from his smorgasbord of occupations. Because he was functionally illiterate, these works offered him not only aesthetic satisfaction; they also had a literary, narrative dimension, brimming with commentary on race relations and natural philosophy, along with psychological insights into human behavior.

In 1983 he lost nearly all his work to a major flood that swept through Pipe Shop. Meanwhile, after the Pullman-Standard closure, he and two of his sons began to make metal patio furniture, forming a cottage business they ran out a shed behind his house.

In 1987 he was visited by the artist Lonnie Holley who was trying to identify older, unrecognized artists and had been told by a friend about Dial. Dial, ever guarded about his works’ meanings, revealed little to Holley, but sent him off with some small, handmade, expressionist fishing lures, which Holley hung in his living room, where collector William Arnett saw them. In July 1987, Holley returned to Dial’s with Arnett, who was interested in seeing more of Dial’s art. Realizing that Dial wasn’t quite sure what Arnett was talking about, Arnett asked Holley to make a piece of “art” in front of them as an example for Dial. Dial then walked into his great-aunt’s turkey coop, next door, and emerged dragging a tall, painted, welded-steel sculpture topped by a stylized steel turkey. From then on he was an artist, publicly.

Dial and Arnett subsequently developed an artist-patron relationship that thrived for the rest of Dial’s life. In describing that day, William Arnett remembers:

“I knew I was witnessing something great coming out of that turkey coop. I didn’t know at the time that it wasn’t simply the sculpture that was special. The man who had created it was a great man, and he would go on to become recognized as one of America’s greatest artists. I can’t think of any important artist who has started with less or accomplished more.”

Dial quickly began to investigate the possibilities of all types of materials and media and developed ever more complex artistic symbols and allegories—as he liked to say, “The more you do, the more you see to do.” The earliest of these multilayered icons to gain widespread notice was the tiger, an image both autobiographical and historical that fused his own life experiences with the struggles of African Americans throughout the history of the nation.

In 1993, he had his first one-person museum exhibition, Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger, a survey of tiger works ranging from the intimate to the epic, presented jointly by the Museum of American Folk Art and the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. He would go on to have numerous other shows, including one-person museum exhibitions at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta; and organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, 2005); and the Indianapolis Museum of Art (Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, 2011—which also traveled to the High Museum of Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Mint Museum).

In 1990 he and his family moved to nearby McCalla, where he gained access to ample studio space, which redoubled his artistic ambitions. The scale of his wall-hanging assemblages could at last keep pace with his ideas. The results were semi-monumental reflections on important episodes in American history. The Last Day of Martin Luther King; Roosevelt: A Handicapped Man Got the Cities to Move; Graveyard Traveler/Selma Bridge. Aesthetic and thematic combinations of daily life and lofty human striving—both grit and symphony—these epics set the tone for hundreds more that would follow in the succeeding twenty years, during which time his art would make its way into numerous museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art; the Smithsonian American Art Museum; and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

Thornton Dial was preceded in death by his wife, Clara, and daughter, Patricia. He is survived by his half brother, Arthur Dial; his daughter, Mattie Dial; his sons, Thornton Jr., Richard, and Dan; and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.