Mattie Clark Ross

About

Raised in the home of her grandparents after her mother died when she was six, Ross completed her first quilt, a nine-patch, at the age of nine. Made to work in the fields from a young age, Ross remembered her childhood: “We did just every kind of task. It was busy. We never did have no time like children go to play now. No time for us to go to play. A few minutes on Sunday.”

In 1919, she married Clint O. Pettway and together they farmed rented land in Gee’s Bend. When the area was divided and sold by the federal government in the late 1930s, they acquired 82 acres for $2,800. Ross took great pride in their “Roosevelt house” and tried to maintain its appearance in the same fashion as when the government built it.

The year following Pettway’s death in 1953, Ross wedded Goldsby L. Ross. Although she never had children, she devoted much of her life to raising those of her brother, sister, other relatives, and a neighbor. She instilled in them the ability to be self-sufficient:

“I taught ‘em how to live, how they gon’ be when they got grown, got out there in the world. “You gon’ need to know this and need to know that.” I said, “I’m gon’ tell y’all what I know.’ And I trained ‘em to piece quilts, to wash, starch, iron, cook, scrub and patch their own clothes.I’d say, “Hon, get your clothes and go to patching. I may be dead and gone. Get you a needle and thread and patch your own clothes.” And they could do.”

Ross’s membership of the Freedom Quilting Bee as its first treasurer was preceded by her participation in the Civil Rights Movement to secure voting rights for Black people in 1965:

"We had the march in '65. We didn't march to Montgomery. We marched to Camden, at the courthouse, for our rights to voting. We had never started voting. We should a did it before then but we hadn't got our rights. We couldn't do it without marching, protesting. We American citizen and it be all these many years and our forebears didn't know nothing about voting. We wanted to do a lot more than they did. We marched and protested, registered to vote."

She proudly remembered meeting Martin Luther King, Jr. when he brought his voting rights campaign to the Bend:

“I shook hands with him and spoke to him. I asked him how he getting along. He said, ‘Doing all right. How you feeling?’ We said, ‘We doing fine.’ And he just say, ‘Well, let us try to do the best we could in non-violence. Don't even carry a hair clamp in your head. Don't carry nothing of any harm. Non-violence.

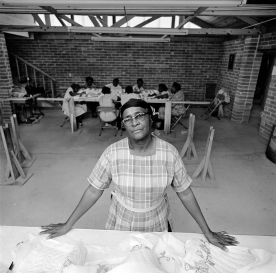

Before the Bee began, she had long quilted in a group setting with friends, with as many as twelve women assisting her at one time to augment her personal collection. Quiltmakers, most of whom were also members of her choir, would converge on her home for an entire day, go home to cook supper, and return for the evening. It followed that a hub of early Freedom Quilting Bee activity was at her home.

Ross fondly recalled her time working with the Bee, which continued until the summer of 1979, when she was in her late seventies:

“I didn’t know anything over there between here and Alberta, but in the quilting bee a lot of us gather and have a good time working there together. We laugh and talk and quilt and do. I learned a lot of good-hearted peoples. And a lot of different peoples come in from way different places, make themselves friendly with us and us makes ourselves friendly with them. We enjoy that so much. I wouldn’t take nothing for being up there at the quilting bee. I just enjoy up there when I was working up there.”

In her eighties, Ross reflected on her life:

"I tell you, what I'm proud about my life is this old age ’cause I never thought I'd live to get old. I'm in my eighties. I'm proud of that. I'm proud of health and strength the Lord let me have, and I'm proud I got to a place where I can't work and still can live if I don't work. The Lord blessed the way so that every month, Jesus-through-the-white-man sends me a check." She refer[ed] with amusement to her Social Security.