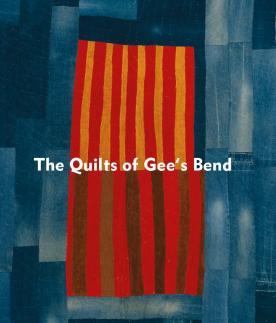

The Quilts of Gee's Bend

Description

The women of Gee’s Bend—a small, remote, black community in Alabama—have created hundreds of quilt masterpieces dating from the early twentieth century to the present. The Quilts of Gee’s Bend tells the story of this town and its art.

Gee’s Bend quilts carry forward an old and proud tradition of textiles made for home and family. They represent only a part of the rich body of African American quilts. But they are in a league by themselves. Few other places can boast the extent of Gee’s Bend’s artistic achievement, the result of both geographical isolation and an unusual degree of cultural continuity. In few places elsewhere have works been found by three and sometimes four generations of women in the same family, or works that bear witness to visual conversations among community quilting groups and lineages. Gee’s Bend’s art also stands out for its flair—quilts composed boldly and improvisationally, in geometries that transform recycled work clothes and dresses, feed sacks, and fabric remnants.

Resembling an inland island, Gee’s Bend is surrounded on three sides by the Alabama River. The residents’ ancestors worked the cotton plantations there, first as slaves, then for several generations as tenant farmers. In the 1930s Gee’s Bend was identified, perhaps wishfully, as “an Alabama Africa” and “another civilization.” Because this tightly knit society had remained mostly isolated from the surrounding world, the people of Gee’s Bend were considered living relics of nineteenth-century life. During the depths of the Great Depression, the federal government intervened to lift up Gee’s Bend—and photograph the ”before” and “after.” Those images, by Arthur Rothstein and Marion Post Wolcott, have become icons of prewar America, and are filled with the women whose quilts the book features.

Together with the exhibition organized jointly by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Tinwood Alliance, the book illuminates three themes in American quilts: quilts as sophisticated design, quilts as vessels of cultural survival and continuity, and quilts as portraits of women’s identities. These women brought a uniquely local flavor to the one visual tradition widely practiced by Americans of every social class, ethnicity, religion, and region. They made an American pastime the literal fabric of their lives—an art that binds the individual’s imagination to family, friends, neighborhood, and the greater community.

The quiltmakers’ narratives brim with humor and resilience. Whether recalling their enslaved ancestors forced to walk from North Carolina to Alabama, a great-grandmother born in Africa, living off the land after their property was foreclosed, or crossing the river to march for the right to vote, the memories of these remarkable women match the eloquence and power of their quilts