Sandy Hall

About

My full name is Sandy Franklin Hall. I was born on September 28, 1920, in Troup County, Georgia, in the place called Cabbageville, near LaGrange. My parents were George and Laura Bell Hall. I attended Kelly Elementary and East Depot High School. In 1942 I married Willow Nell Moon, and then went into the service.

All of us black soldiers were put together in one unit. We got sent over to England and then to Glasgow, Scotland. In Glasgow, we stayed up on a hill away from the rest of the troops. They wouldn’t let us bivouac down near the town. They put us out in the woods and restricted us to post. Only the white soldiers could come and go.

In Glasgow, at first, they let us go down to some of the beer pubs nearby. The girls were friendly and invited a lot of the black boys to come meet them. The white soldiers would tell the girls, “Don’t mess with them niggers, ’cause they’re dangerous, and they got tails like a monkey, and they’ll rape you and hurt you”—anything to keep the girls away from us. But the girls found out different.

I was in the ETO, the 3rd Army. I was a mess sergeant with the rank of “Staff.” I got sent over to France in the invasion, and that’s when I saw my first combat. I was sent to shore before the other ones. I had to get there first to start making coffee. I don’t remember much except the noise. I was scared, but not as scared as I should have been.

I saw more combat later on in France, a place called Soissons, and then in Belgium. When we went to invade Germany, I was there, too. We were three days waiting to cross the Rhine. I never made so much coffee in my life. Doughnuts, too. We had our first fatality of one of our men there. He had a pass and went into town, and was shot and killed by a German sniper. That stopped the passes. We stayed close together after that and only went out in large groups. We still had this unit of all black people, and the company commander and his assistant were white. There were some black officers under them.

When the war was over, we was in Belgium but got sent over to Germany, taking trucks around to get rations at supply dumps. We were heading to a dump in a truck, a weapon carrier, and the driver, Corporal Harper, a short black guy, saw a sign pointing to a place he’d heard was a concentration camp. He said to me, “Sarge, let’s go up there and see if we can get a look at it.” We got there and found French soldiers guarding the place. We had to bribe them with cigarettes to get in there. Everywhere we would go, we would carry cigarettes. Cigarettes, sugar, coffee, and chocolate candy. That’s what they all wanted, and it would get you girls or anything else. So when we got in there, one of the fellows with us, McAlister from Louisiana, he could speak French words, so he got information from the French soldier and gave us a tour, six of us. The war was over then, couldn’t have been more than a week.

First thing I remember seeing was this big trench dug to throw the dead in. You couldn’t stay there long because some of them had been dead a long time. The smell. Then we went on down further and saw the ovens, and another building that a long time later on some white soldiers told us was where some experiments had been done on people. The mortuary.

I can picture this: After we got off our truck, we were afraid the stink of the dead bodies would get into our truck and stay there. The bodies were piled up, just pile after pile of bodies, and I thought, “How could one human being do this to another?” I couldn’t understand it. I was only a twenty-something-year-old colored boy, hadn’t never been out of Troup County. Every now and then we would see a finger twitch, or a movement in a body, and we’d holler to the people identifying the bodies, and got out of there. Scared. All us little colored boys didn’t know nothing.

I got sent to Berlin in charge of feeding allied troops coming into Tempelhof Airdrome. After that, we got shipped back on trucks to the port of debarkation in France. When we got to France, we got loaded on boxcars. The saying was “eight horses or twenty men” on each of the boxcars. There was white and black soldiers both. It was the first time we were ever integrated, going back on the boxcars.

I was in charge of my boxcar. We made very many rest stops. At every rest stop, we got out, emptied our bladders or whatever, and got coffee and doughnuts from the French ladies, and also some K-ration food We carried our own mess kits, and after we ate, we washed them in big drums of hot water. The drums had to be emptied, and it was my job to order soldiers in my boxcar to empty the drums.

We had a tall, slender soldier from Copperhill, Tennessee, looked a lot like Gary Cooper, the Western actor. He liked to tell us about this big old sign in Copperhill that said, “Nigger, read this and run, and if you can’t read, run anyhow.” When it was his turn, I told him to empty the drum. He refused. He said he was not going to do it because he had never took an order from a nigger, and if his mother and father was living, he said, “By God, my maw and paw is dead and they would turn over in their grave if they knew I was sleeping on a boxcar with a nigger.” The other black guy in the boxcar, John Bethea, he looked like Jack Johnson and said, “Mother———er, you better empty that drum or I’ll beat your mother———ing ass.” He was a nice boy from then on.

I was discharged at Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia, January 1, 1946, and sent on a bus to the bus station in Atlanta. We thought that since we had been over there and fought for our country that we’d be able to get off that bus and go inside the bus station and eat something, ’cause we were very hungry. We expected to be treated nicely. But when we walked through the front door of that station, all hell broke loose. We were stopped right at the door. “Go around that way, that’s the nigger way.” They were very serious. A lot of them. I didn’t eat until I got down to LaGrange.

The white folks were geared for that. They thought, “When those niggers get back, they’re going to expect to be equal, but we’re going to show them their place.” They showed us our place, and we stayed there until Martin Luther King’s days.

I got back to LaGrange and it was cold and nasty, and I had to carry a heavy duffel bag all the way out to where I stayed. You wouldn’t look at no white taxicab. There was one black cab driver, a World War I veteran with a messed-up arm—that’s why they let him drive one—but he wouldn’t carry nobody out to those muddy streets in Cabbageville.

I got there, and my wife. Willow, come running to the door. She had a boyfriend. That night I said to myself, “I can’t handle all that. Of course, I figured it out that she didn’t have no interest in me neither, so I went to Atlanta and rented a room with two old friends in an apartment on Houston Street. I bought myself a Buick, a 1940 two-door Buick Special from Ward’s Used Car Lot down around Spring Street.

I got hospital work in Atlanta and stayed there trying to make ends meet for a number of years. I figured I’d do better back home, so I drove down to LaGrange. I ended up working for Troup County Hospital from 1948 to 1959. I got my license there as a nurse. I took care of a good white man there, Mr. Skeet Johnson, who was a man who did so many good things for black people. I went to New York in ’59 and worked a year at Farm Colony Hospital for the Aged. I left there and went to Miami.

I got to Miami and got me a job at the Children’s Variety Hospital and rented a room at the Imperial Hotel. The hotel was owned by a Jew, Johnny Golden. One day he saw me coming down the steps, called me to his office, and told me we wanted me to manage his hotel. I told him I’m a nurse, not a hotel man, but he said he knew I got along with people and would do a good job. He talked me into it. He gave me a lot of respect and trust, and I treated him fair. The white people had started clearing out of that area when they saw it was going to be integrated. The hotel started out white, got integrated little by little, and ended up mostly black. I ran that hotel for thirty years.

My reputation had gotten good. “Sandy Hall is a colored man you can completely trust.” Johnny Golden recommended me to his friends from Chicago, and I ended up managing a lot of properties for people. I managed property I wouldn’t even go near because of the whores and pimps.

I left Miami after divorcing my sixth wife in 1989. I paid in advance to give her a college nursing education. I told them, “If you take her and she don’t graduate, you won’t owe me nothing.” She did graduate, and I got her a job at the Miami Jewish Home and Hospital with the wife I had before her. They got to be big friends. But she went to too many “happy hours.” She wrecked every car I gave to her. The last one was a Cadillac Sedan De Ville. She hit a Cuban woman, and they put her in jail. I paid her debts before I left, took a few dollars for myself (but left her with most of what I had), and drove north on U.S. 1. I was a little bit crazy by that time and didn’t know where the hell I was going. I was in a cheap little motel in West Palm Beach. I woke up and thought, “I got to get out of here.” I paid some Mexican migrant workers to load up my car and headed up the road. I don’t know exactly how it happened, but I ended up in Seattle, Washington.

I hadn’t had no reason for going to Seattle, so I turned around and came back all the way to West Palm Beach, right where I started. I called my sister in LaGrange, Georgia, and talked her into letting me come stay with her. So I got a room at an apartment house. The owner wanted me to run it for him, and I did that. Then my daughter in College Park wanted me to manage a home for the aged she and her husband had anticipated buying. I came up to Atlanta, but they didn’t buy the place, and I rented a room on Highway 29 in East Point. When the landlady started making eyes at me, I told her, “Look, I’ve had enough women for one lifetime,” so I packed my bags and left.

I called my sister back in LaGrange, and they told me she had moved to Atlanta. I came to Atlanta and found her living in the Lutheran Towers. I asked her how to get in this place. She said to fill out the form and wait for about six months. I filled out an application, talked the manager into considering it right away. He said give him an hour. He came up to my sister’s and told me to move in. Later that year, they had their election for president of the residents’ association. They elected me out of 250 tenants. I was the first black to have that job. (I had been involved before with being the first black man. I had been the first president of the NAACP in Troup County. I was the first black elder of Westminster Presbyterian Church in Miami.)

I started episodes of depression right about 1992, and, man, they were terrible. I would find myself walking through the house crying, and I didn’t know why. I’d look at the window and say to myself, “Just dive through it, like Superman, and you won’t cry no more.” All I could think about was suicide. I was walking one day all over Atlanta. I ended up on an expressway bridge and decided to jump. A man standing across the street yelled at me, “Hey, you don’t want to do that.” Well, that kind of woke me up, interrupted my trance, and I went over to Georgia Baptist Hospital and found a doctor, a cardiologist named Dr. Lipman. Eventually, I ended up with Dr. Ball, a lady psychiatrist. I got sent over to a psycho ward across the street for depression. “Talk Therapy.” I got to Dr. Ball and told her to get me out of there. They were starting me in “sessions,”like a first grade child, talking and playing and drawing. I drew something like a stream running over a rock and forming a waterfall. The lady said, “Yeah, you need to keep doing that. It’s good therapy for you. See all that red? It means you’re hurting.”

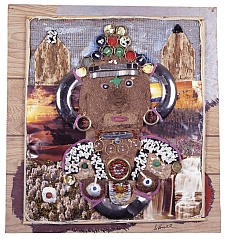

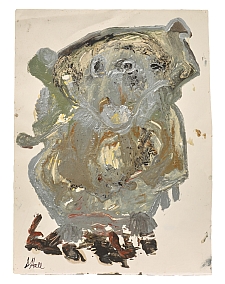

When I was discharged, I walked home and picked up some little black dolls behind an old building, took them home, and made that Little Drummer Boy piece. After that, I kept walking and finding stuff and making tilings out of it. I had considered making things before, but there never was any time for it. I was glad to try to let my head relax and come up with different ideas. I knew that my depression, if I allowed it to, could take complete control. I thought I knew how to control it, by making paintings that got the feeling out of me, mostly explosive, mostly angry. Most of my first paintings were about depression. Or about the concentration camp. After I visited it I should have been able to leave those thoughts behind. I had been a nurse, had seen suffering and death, but those thoughts of that massacre never left me. They stay with you. You just want to put a bomb in your head and blow those thoughts out.

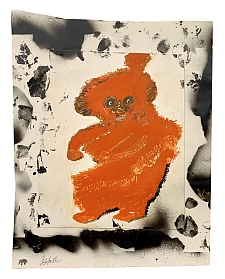

I draw a lot of animals. I watch a lot of sad movies about animals and cry like a baby. I tell myself I ought to be ashamed, a seventy-seven-year-old man sitting up here crying. Then I get up and make art and wait for the depression to abate. If I don’t, I might jump out of the window. I am going to conquer myself, I am going to overcome my problems.

Art has definitely been a good form of therapy for me. I believe this now: it allowed the good Lord to help me to help myself.

When I’m doing my artwork, I’m in hopes that someone will view it and get the same kind of happiness, the same glowing feeling that I get doing the work myself.

Even the way I fix my room, it’s a big arrangement of art—art I have made, or art I have found made by other people, or art I bought at yard sales, or things given to me. It is a soul-to-soul connection between me and other makers of things. When people come to visit me, their faces often light up, and they have an appreciation of things here. I make sure that every space is covered, as near as I can. Everything in here fills a void that is in me, living alone. I look up at every object in here, and my mind gets to work thinking about it, imagining what it is, or where it’s been.

I appreciate balance, and when I'm making things or arranging things, I believe everything must be in harmony with each other. Even in abstract art, that may be confusing to other people, it got to be a conglomeration that balances out. The big round painting I look at from my bed, it is supposed to represent the feeling of a person's soul, it does its duty to bring in balance the experiences of that person who is looking at it. There's a poem I had to learn back in about the fifth grade in LaGrange, Georgia, and part of that poem said

All are architects of fate,

Working in these walls of time.

Some with massive deeds of great,

And some with ornaments of rhyme.

That poet, he addresses my everyday life, he makes me know that I am important. I fit into the category—an architect of my own walls, with my own rhymes. Art is my own rhythm.

This account of Sandy Hall’s life was taken from interviews with the artist conducted by William Arnett in 1997.