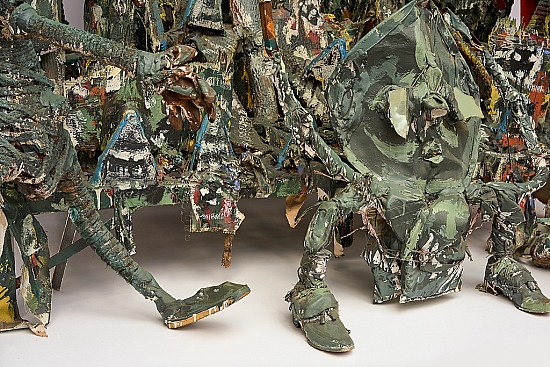

Dial watched some of the O.J. Simpson murder trial almost every day it was televised and began creating artworks about the trial and events preceding it. "The Color of Money" consists of six sculptures and two assemblage paintings, all dollar green, about the commercialization of Simpson's plight. The second was Hard Bed, as in the expression, "He made his bed hard and now he has to sleep on it." This two-sided sculpture, constructed of old wood and scrap metal on a bed frame, resembles, from one side, a rural community of shotgun houses (perhaps intimating Simpson's humble origins), and, from the other, a jury box.

To Dial, O.J. was a classic trickster (though an inadvertent one), not unlike heavyweight champion Jack Johnson almost a century earlier. Marrying a white woman, as O.J. and Johnson both did, remains profoundly disturbing to every status quo. O.J.'s irritation of white America could also therefore qualify him as an African American culture hero; however, Simpson's life has also been in several ways a renunciation of his blackness, a choice that provokes contradictory emotions among many African Americans. As Purvis Young might say, Simpson is "one of those black guys the white folks show us to help sell us their products." Dial nevertheless hoped Simpson would be acquitted of the murder of his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, because the issues of guilt or innocence seemed largely beside the point: If Simpson were guilty and won acquittal, perhaps that would help balance out, symbolically, the countless convictions of innocent blacks. Dial believed Simpson's guilt could neither be proven nor disproven; the accused was instead putting America’s racial stereotypes on trial and forcing all Americans to become judges—of themselves.