Dinah Young

About

I was born here in Hale County somewhere, in a old house burned down, over where I call "the swamp." I don't know exactly where. Talk to the lady up the street. She knows and I don't. She says it was somewhere down here in the woods somewhere, in a house that burned down. I was born in 1932. My mama did tell me that I was born anemic and had pneumonia, and the doctor had to come to feed me three times a day.

My mama come out of fifteen children. My grandmama had been a white man's daughter, and my mother had the white folks' hair. She had fourteen children herself, I think she said. We got plenty of Indians back in the family but I can't rake them up. Everybody else got that long straight Indian hair, and I just got me these old knots. I don't know why, they just popped out on my head.

Growing up, it was horrible; it was terrible. We had a lot of us, and the parents didn't know how to discipline. They was children themselves, if you want to know the truth. There's a adult part and a child part in everybody, and when adults act worser than a child, they can't raise a child. You have to have stability and attitude about you to raise children, to know how to make picks and chooses between them, and everything went bad. And never did stop going bad. Except I always seemed to be able to get to myself and correct myself.

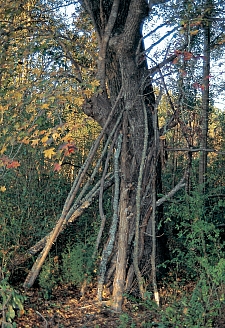

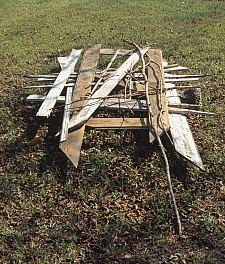

As we grew on up, it stayed rough. Seem all we do was haul wood and water. Daddy was a carpenter. We all farmed. So we just suffered along the way, and we had to be our own parents. We had everything to do, and it was really hard. We always had to go in the woods and we had to saw trees down—big trees. We had to saw them up and put them on the wagon that the damn horse wouldn't pull. And every time we would put it on there, she wouldn't pull away. She would drop to throw the wood off, and when the wagon was empty, she'd go on. We reloaded it, and reload again, till we got home. She keep throwing it off, we throw it back on. We used to struggle, and saw our wood, and work like men—and the two boys wouldn't do a damn thing. The world's worse. We used to have to go down to the creek, haul our wash water. We didn't even have a well. We walk two, three miles over to a guy's house and got our water 'cause they had a well. Things we shouldn't have done we had to do. It was our duty.

We walked to school—three, four miles. The weather wasn't like it is now or we wouldn't have got nowhere. It's too hot now, and too cold, and it rains too much, or not enough. I walked from way up there to way down here. I went to the ninth grade here—it didn't go higher than the ninth—and then we had to go to Hale County to the training school. We had to ride the bus to school in Greensboro. But I just put it damn down and went to Buffalo, New York.

I had a cousin was real sick in Buffalo, New York, I went there to see about. I stayed awhile, two years or so, until she got back going. I come back—I was about twenty then—and I went to Birmingham. See, I had to leave here in '53, 'cause they had taken all the land and the crops away from peoples where nobody couldn't make a living. So you had to go somewhere to get a job. I went on my own to Birmingham.

In Birmingham, well, I played around there. Mostly I catered different parties, arranged big trays of food, and worked for people doing jewelry shows and things, and did housekeeping and nursing. Too damn much. I did cafeteria work, restaurants, and nightclubs. I worked for a wholesale jewelry company and did displays over in Atlanta, and I had to get all that together and decorate this and that, and table decorations to make. And I made a whole lot of corduroy things to go on the display tables and little carts on rollers. And all the holidays I was catering parties. It just goes on.

And I came back here. I always said if I ever got back to myself, God knows I'm going to stay. And I found two older peoples staying in this old house. I met them April 7, 1991. I was near sixty years old. They asked me to live here and take care of them. I also found that other house 'cross town, and the owner let me move some of my stuff in there. The woman that owned it, she lived in Akron, Ohio, and in '98 she went to bitching about how bad I kept that raggly damn house, and she tore up all my stuff. I had to carry the rest of the damn stuff over here and store it in the yard. I just want to whip her black ass—throw some gasoline on it and put a match to it—but it wouldn't bring anything back.

It's okay here. Some things about it could improve; the food's bad, so bad, and the chemicals in the food have changed my whole life. My hair turned to grass. And I never was so ugly, until I got arthritis. Oh, Jesus, I wish I could show you a picture of myself. I found a old picture a few years ago and thought, That's a beautiful woman, and put it back, and found it again the next year and realized, Ah, that's myself.

Insects bad around here. Mosquitoes so bad. They live a long time when the weather's bad. You think they dead when the cold come—go back there and can't even find a little old one—then it warm up, they thaw out, they get up and go. Gone. That's how I learn. I pay attention. And the little lizards—I thought they going to die because of no food in the cold. And I see them later and I say, "I thought all of y'all got caught in the cold and couldn't survive." But, I say, "Jesus, they're just like the frogs. Whenever it warm up, they go." And I was glad to found that out because it's been some nasty cold. Days and nights. I don't worry no more, not about the little creatures. Now, with all this rain you can't cut the grass when you need to. Do mosquitoes bite you like they bite me?

It's such a hot spot here so much of the time. During the winter you might freeze back in this little end, because the house is so raggly and it's shady. But we have so many hot days in the winter. It don't never stay winter. It switches to a hot day today, and a cold, and a hot day today, and you got to keep up with the weather, and then it switches.

So I been here ten years. Slavering. Nothing but slavering. You can't do nothing here, and can't get away if you want to. I waited on them two older peoples. One of them's dead now; the lady died last May. The old guy's in the home up in Greensboro. He'll be ninety-six, June coming. He don't even know me now when I go see him. I'll be here till I be buried. I'm not going to move no more. The peoples that own the house be gone now: on her side, the nieces and nephews, in Detroit. They has no interest in it. They didn't even come pay to move the body when she passed. The state buried her; they go in and bury you when the family denies you.

I take care of some yards around here. Used to do five of them. Only two now. They take care of me for my work. On the holidays they feed me good meals. We always communicated that way. I got a neighborly arrangement. I meant to ask you to bring me some animal crackers.

I'll be here when you come back next time. Where I'm going to go?