A History of Gee’s Bend

How curious a land is this—how full of untold story, of tragedy and laughter and the rich legacy of human life; shadowed with a tragic past and big with future promise.

—The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois

Gee’s Bend takes its name from Joseph Gee, a North Carolina enslaver and planter who, in 1816, acquired 6,000 acres of land along a horseshoe bend in the Alabama River and established a plantation with 17 enslaved people. The Gee family operated the plantation until 1845, when, to settle significant debts, they relinquished ownership, including 98 enslaved people, to Mark H. Pettway, a relative, enslaver, and then sheriff of Halifax County, North Carolina. The following year, Pettway relocated to Gee’s Bend, transporting his family and furnishings in a wagon train while 100 enslaved men, women, and children were compelled to journey on foot from North Carolina to their new life in Alabama.

While Gee left his name on the land, Pettway left his on the people. In Gee’s Bend, as on plantations throughout the South, enslaved people were forced to assume the owner’s surname, a fact that can obscure otherwise diverse family backgrounds. Speaking of his great-grandfather, Hargrove Kennedy observed,

Following the Civil War and emancipation, a system of tenant farming, or sharecropping, took hold in Gee’s Bend and throughout the South. In this arrangement, landowners permitted formerly enslaved farmers to stay on and cultivate their land, receiving a portion of the harvested crops in return. Unpredictable harvests, coupled with unscrupulous landlords and merchants, made this a highly disadvantageous arrangement for farmers, leaving them, as it was intended to, perpetually in debt. While ownership of the Pettway plantation would change numerous times in the decades following the Civil War, the exploitative tenant farming system persisted.

The Great Depression marked the most significant period in the community’s life since emancipation. As cotton prices fell throughout the 1920s, farmers in Gee’s Bend were forced deeper into debt. In the summer of 1932, a Camden merchant who had been advancing credit to more than 60 families in the Bend died. That fall, his estate foreclosed on their debts and organized a raid on Gee’s Bend, seizing anything of value, including livestock, farm equipment, and stored food. The raid drove an already impoverished community into complete destitution, forcing them to forage for berries and hunt game to survive the winter.

Responding to the plight of struggling farm families throughout the U.S., President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Resettlement Administration in 1935. While its initial intervention in Gee's Bend was modest, consisting of small loans to farmers, it quickly escalated into one of the agency's most radical and ambitious projects. In 1937, the federal government pieced together and purchased the former Pettway plantation, some 10,000 acres. The Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration, then provided low-interest loans to families in Gee’s Bend to buy land and build houses. It was through this process that Benders came to own the very land worked by their enslaved forebears.

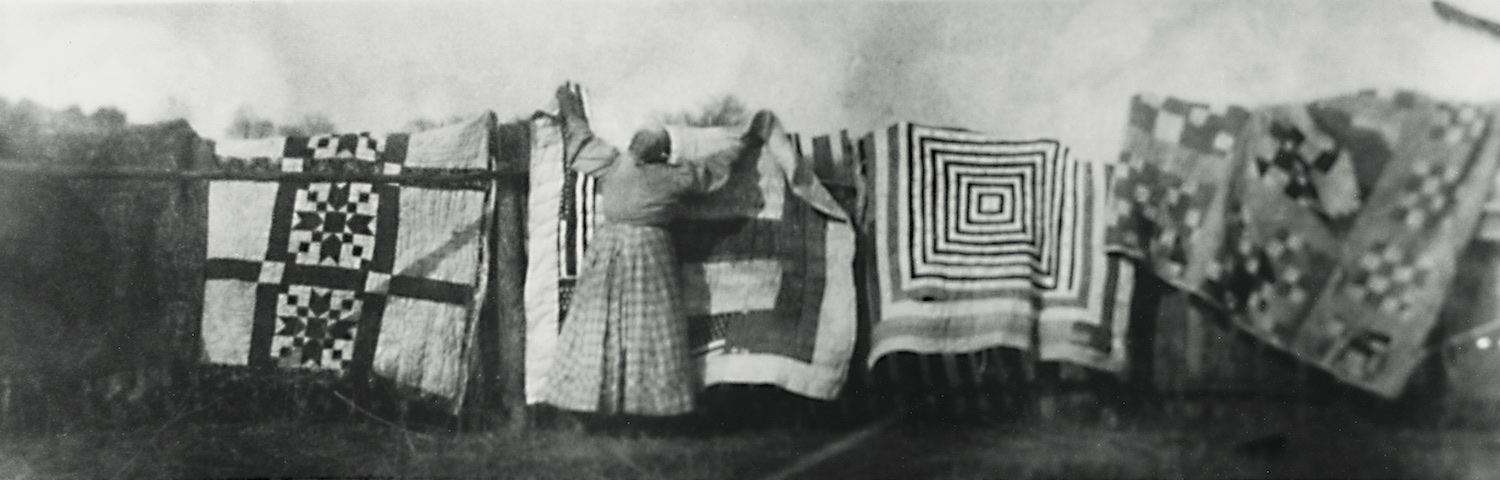

With additional federal assistance, a cooperative farming association called Gee's Bend Farms was established, and in the years that followed, a school, medical clinic, general store, warehouse, gristmill, and cotton gin were built, along with nearly 100 houses that residents could purchase with low-interest government loans. At a time when two-thirds of tenant farming families in Alabama moved each year, families in Gee’s Bend could remain on the land where most of their parents and grandparents had been born. Cultural traditions like quiltmaking were nourished by these continuities.

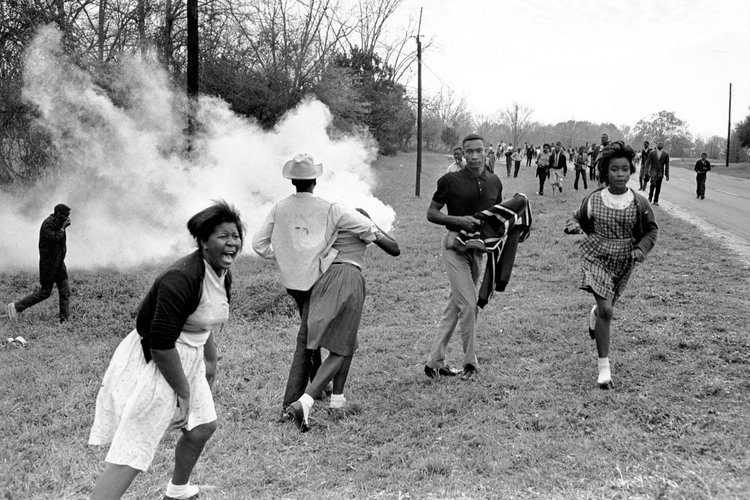

In the early 1960s, in response to growing participation in the Civil Rights Movement, white officials in the county seat of Camden discontinued ferry service to Gee’s Bend, effectively isolating the community and cutting it off from basic services. Wilcox County Sheriff P.C. “Lummie” Jenkins reportedly said at the time, “We didn’t take away the ferry because they were black; we closed it because they forgot they were black.” Ferry service between Gee’s Bend and Camden would not be restored until 2006.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. carried his voting rights mission to Wilcox County in February 1965, African Americans comprised nearly 80% of the population, yet registration of eligible African American voters in Wilcox County was 0%. On the evening of February 16, 1965, King made a trip across muddy, unpaved roads to Gee’s Bend, where he addressed a packed crowd of 300 at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church.

“I come over here to Gee’s Bend tonight to tell you that you are somebody! I come over here tonight to tell you that you are God’s children. And that every man from a bass black to a treble white is significant on God’s keyboard. Don’t let anybody make you feel that you don’t count … I want you to know that you are somebody, and you are as good as any white person in Wilcox County!”

Many in Gee’s Bend braved the threat of violence to march with King in Camden, including Aolar Mosely and her daughter Mary Lee Bendolph, who recalled him drinking from a whites-only fountain. "I never saw a black person do a thing like that," she told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times. "I was so glad." Others, like Lucy Mingo and Estelle Witherspoon, joined King in the march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21-25. “No white man gonna tell me not to march," Mingo declared. "Only make me march harder."

At King’s public funeral following his assassination on April 4, 1968, his casket was drawn through the streets of Atlanta by two mules from Gee’s Bend.

On March 26, 1966, more than 60 quilters from Gee’s Bend, Alberta, and surrounding communities met in Camden’s Antioch Baptist Church to found the Freedom Quilting Bee (FQB). One of the few Black women’s cooperatives in the United States, the FQB quickly grew into a robust organization, landing contracts with New York decorators and with Bloomingdale’s to produce made-to-order quilts, helping to inspire a national revival of interest in patchwork.

In 1969, the FQB acquired 23 acres of land on County Rd 29 in Alberta and built a 4,500-square-foot sewing center, allowing it to expand its offerings to include direct-to-consumer sales. The new building also allowed the FQB to extend services to its members and surrounding communities, such as daycare, an after-school tutoring program, and a summer reading program.

Beginning in 1972, the lifeblood of the FQB became a contract with Sears Roebuck & Co. to produce corduroy pillow covers, supplemented by sales to Bonwit Teller and Saks Fifth Avenue of easy-to-assemble, small-sized baby quilts. The Sears contract sustained the FQB for almost twenty years as the demand for quilts ebbed due to changes in fashion, automation, and competition from cheap, mass-produced foreign goods.

In its time, the FQB brought significant benefits to the area in the form of jobs and leadership opportunities for the community’s women. At its height, it had 150 members, making it one of the largest employers in the area. Nettie Pettway Young, whose work for the organization spanned five decades, recalled, “The Bee was the first business Black people in Wilcox owned. It was the first time I knew I was special, the first job I had—excusing cotton picking.”

For generations, the women of Gee’s Bend have been creating patchwork quilts by piecing together scraps of fabric and clothing in abstract designs that had never before been expressed on quilts. Their patterns and piecing styles were passed down over generations, surviving slavery and Jim Crow. Enlivened by a visual imagination that extends the expressive boundaries of the quilt genre, these astounding creations have expanded the realm of Black visual culture and opened a door to new understandings of American art and history.

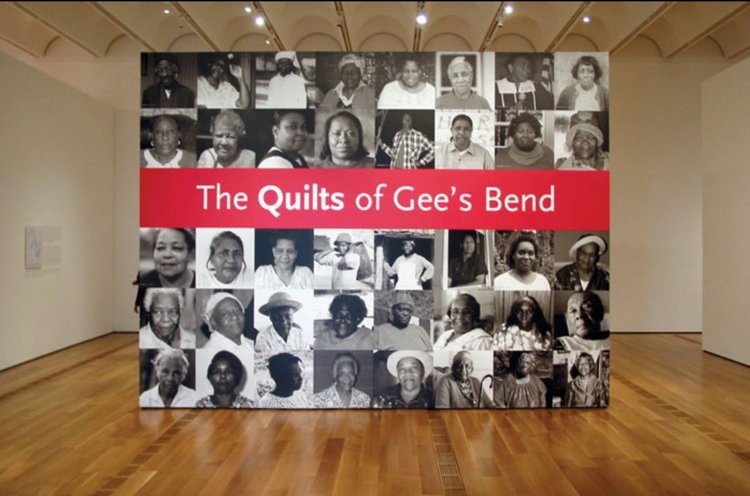

In 2002, the seminal exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend debuted at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, celebrating the artistic legacy of four generations of Gee’s Bend quiltmakers. Hailed by the New York Times during its display at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art as “some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced,” the quilts were displayed at 11 other museums nationwide. Since this first exhibition, Gee’s Bend quilts have been exhibited in museums worldwide, including, most recently, at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark.

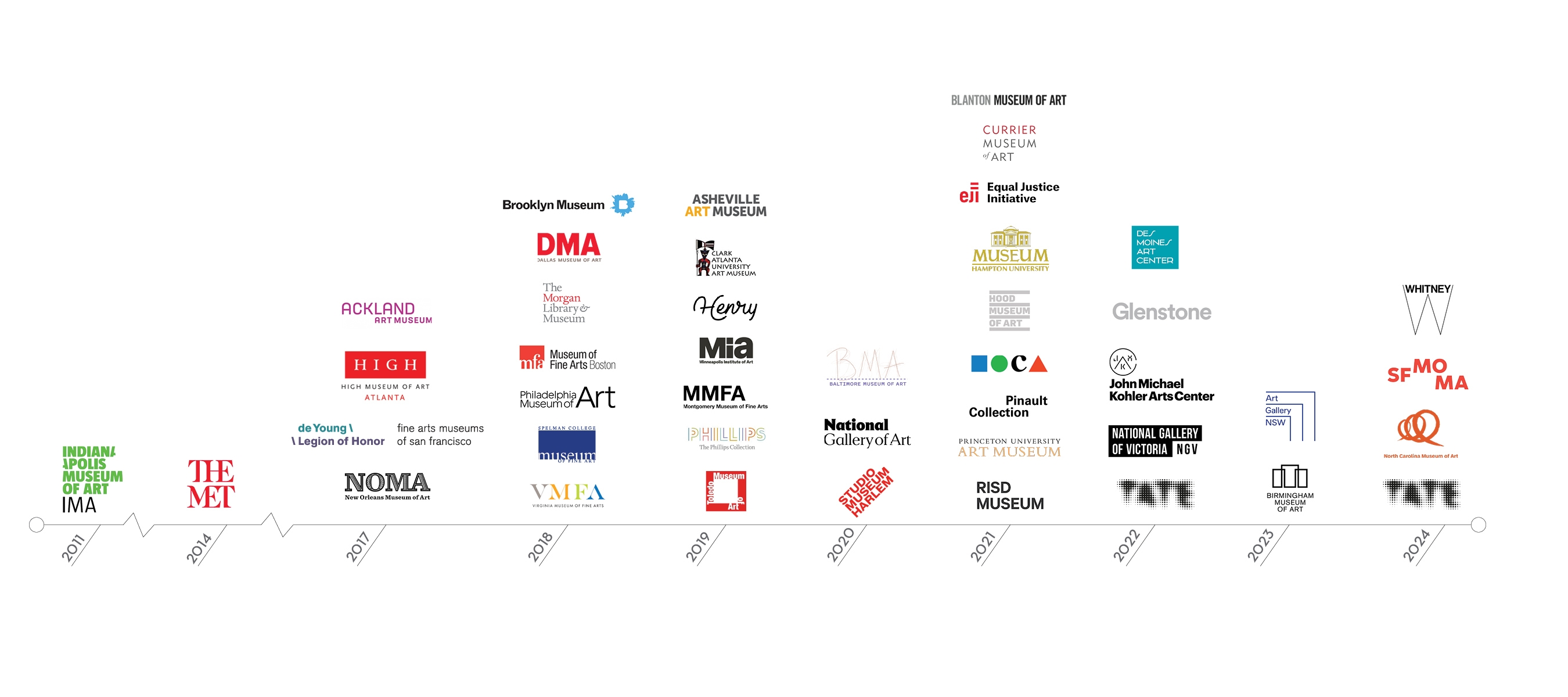

In 2016, Souls Grown Deep began a process of transferring artworks from its collection into the permanent collections of museums worldwide, with the goal of diversifying museum collections and securing the place of Black artists from the American South in the canon of American art history. Today, Gee’s Bend quilts are in the permanent collections of over 40 museums on three continents.